In a post-crisis era, Europeans must focus on efficient and smart regulation in Securities Financing Transactions (SFT) to support competitive financial markets. This can be achieved but requires regulatory attention to solve several specific and identifiable issues.

In his Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System, US President Donald Trump asked to “Make regulation efficient, effective, and appropriately tailored”.[1] With several hundred pages of reports now published and over 200 proposed changes to financial rules, US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is keen to assert that the report is not calling for a repeal of Dodd-Frank regulations, rather, that “by streamlining the regulatory system, we can make the US capital markets a true source of economic growth which will harness American ingenuity and allow small businesses to grow”.[2] Quite typical for the US and somewhat unusual to European ears, he puts real economic growth – or the lack of it – in direct context to inefficient financial regulation: “The US has experienced slow economic growth for far too long”.[3] While the politics behind these statements can be debated, the reality is that the US is moving to loosen financial regulation.

Europeans may be at a different juncture, given that the European debt crisis peaked four years after the financial crisis with the repercussions still being felt, particularly in southern European countries. Moreover, Europeans had to start almost from scratch with no pan- European approach in place. The result was insufficient regulation that was incomplete and fragmented across the Eurozone capital market. Europeans had to create regulatory agencies and come up with new financial regulations on short notice that applied across the whole Eurozone. Where this was not politically feasible or where progress was not fast enough to arrest a spreading crisis, the ECB had to fill the void and step in.

However, with the state of emergency over and the US spearheading the debate, Europeans cannot afford to be complacent and must strive for a regulatory landscape that is not unduly restraining real economic growth. For this to happen, regulation needs to be:

- Efficient in reaching an objective at the minimum cost, with “cost” being defined in a broader, holistic way. For example, taking into account the opportunity costs to support real economy growth.

- Holistic and consistent in preventing redundancies and overlap across the regulatory landscape.

- Helpful in reducing unintended consequences and conducive to macroprudential objectives like stability or sustainability.

Efficiency of European SFT regulation: why the LCR makes sense

To support the development of better European policies for SFM regulation, Finadium, a capital markets consultancy, interviewed a group of senior level SFT market participants in November and December 2017. The objective was to hear their views regarding the state of affairs of regulatory initiatives in SFT markets and how to improve regulation, making it smarter and more efficient.

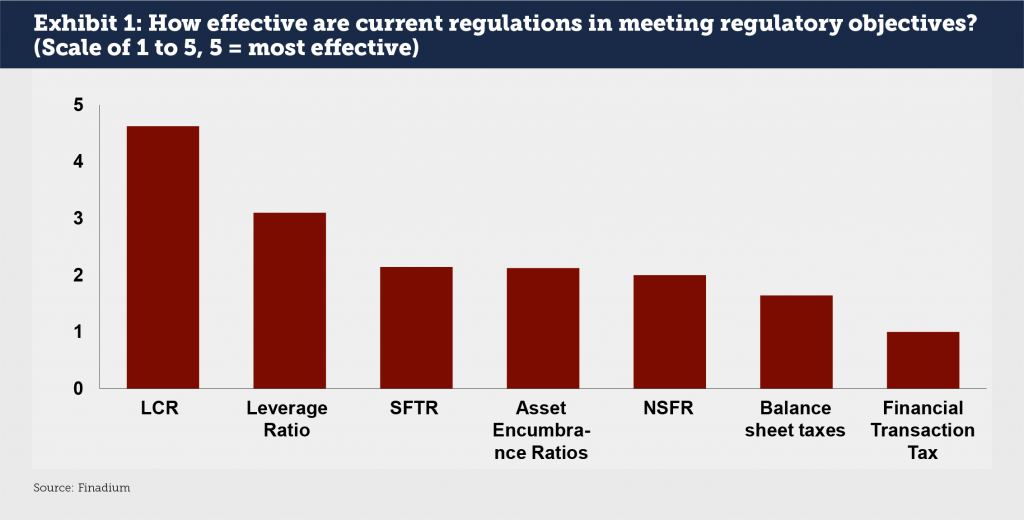

SFT market professionals reported their views on the efficiency of certain regulatory instruments, meaning achievement of regulatory ends at minimum cost, on a scale from 5 (most effective) to 1 (least effective). The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) has managed to score as one of the most effective instruments in the modern toolkit of financial regulators (see Exhibit 1). The Leverage Ratio (LR) is still considered to be efficient, while SFTR, Asset Encumbrance and NSFR are already lagging behind. Balance Sheet Taxes and eventually the FTT lag far behind in terms of effectiveness, with most market professionals hoping they will just disappear in the drawers of the regulatory cupboards.

Now, can we use these results to establish some guiding principles as to what makes regulation efficient? What can we learn from the success story of the LCR? And what do initiatives like the Leverage Ratio or SFTR lack?

The LCR has addressed a real issue in financial markets. It can well be argued that (regulatory) liquidity was absent from pricing methodology before 2008. Liquidity mismatch methodology in many financial institutions was poorly understood and liquidity mismatches were neither properly measured nor managed. Liquidity was the missing link. There are several academic papers pointing towards too much reliance on short-term wholesale funding markets in the run up to the financial crisis and a subsequent evaporation of funding sources when the crisis struck.[4] The LCR has addressed some of these issues in a very efficient way with repo, securities lending, and SFT markets now helping actively in price discovery for (regulatory) liquidity. Even CCPs have taken note and started to set up LCR eligible baskets, establishing marketplaces and transparent market prices for (regulated) liquidity.

The LCR has a clear and well defined regulatory objective. It is understood that the LCR reduces ultra-short-term liquidity mismatches as well as increases reaction time for regulators as they try to work out a solution for a bank facing a liquidity / funding crisis.

The LCR has clear and well-defined means to achieve its objective. LCR eligible assets, their haircuts, and eligible maximum contribution to the fulfillment of the LCR are well defined. The formerly secret science of mismatch calculation is now state of the art in any Treasury department. Most institutions operate some Funds Transfer Pricing (FTP) methodologies to ensure that consumers of liquidity are being charged appropriate prices and run collateral optimization projects to ensure that liquid collateral is not wasted within the institution.

The LCR has established a level playing field for price discovery of liquidity in money and SFT markets that was not in existence before. Both FTP and collateral optimization are now standard instruments. But, before the crisis, hardly anybody would have spent much money on mismatch calculation, FTP or collateral optimization. The impact of the LCR on the development of these instruments and methodologies cannot be overstated.

Judging the other regulatory initiatives against the criteria of efficient regulation explains to a large degree why they are considered less effective or outright ineffective.

Where the Leverage Ratio gets it wrong

Before the crisis, balance sheet consumption did not command a price. Like the availability of wholesale funding, it was a free resource, especially for large institutions. The LR has changed that for the right reasons. If you take an institution’s overall balance sheet size versus its risk absorption capacity as a proper indicator of real economic risk, constraining leverage in good and optimistic times is a logical answer. Hence, regarding the first criteria outlined above, the Leverage Ratio does seem to address a real issue in financial markets.

The LR also has a clear regulatory objective: either reduce your balance sheet or increase your level of risk absorption capacity and / or capital. And since the inception of the LR, bank leverage seems to have come down as well, with 74% of the participants of the Finadium survey stating that they manage to a Leverage Ratio of more than 4%, where the regulatory requirement is currently at 3%.

According to the Finadium survey, the cost of capital for most market participants is higher than 10%, which means that for most respondents the LR does induce some real economic cost for balance sheet consumption. This shows that the LR has teeth and creates a need for active balance sheet management.

But does the LR really help in reducing systemic or idiosyncratic economic risks? Unfortunately, this is where the buck stops. In European markets, repo collateral consists predominantly of government bonds (70%) and is ultra-short-term with 80% of repo transactions trading shorter than six months, according to ICMA surveys. Moreover, repos are often traded in matched books, with assets and liabilities cancelling their respective risk positions as is the case with derivatives. However, in contrast to derivatives, repos attract a full LR charge, roughly equivalent to their notional amount. As a result, managing or better massaging the LR number by means of government repos (ideally GC repos) is the cheapest tool. Little wonder that repo has become the main working horse for managing the LR.

And this is where the LR does get it wrong. Originally drafted to reduce leverage of risk exposures versus risk absorption capabilities, the LR leaves both of those objectives unchanged while massaging the figures by way of a nearly riskless instrument and penalizing low risk instruments in general. It can even be argued that it incentivizes more, not less, risk taking against a certain amount of capital. Consequently, the LR or the change of the LR does not really convey a lot of information on real economic leverage, nor does it limit idiosyncratic risks or fence in systemic risks. It does not tick the box of the third criteria: the LR does not have a clear and well-defined means to achieve its objective.

Some experts argue that the LR is efficient because it is meant to reduce repo activity in the first place. However, I would point out two caveats. First, even in academic papers, this mainly applies to repos with credit collaterals, not with highly rated government collateral, a market that held steady even in the darker days of the financial or European debt crisis. Second, it still compares apples to oranges. If regulators had in mind to reduce overall repo activity, they should not have conflated the idea of leverage in real economic risk exposures with repo activity in short maturities and government collaterals. They should have made these issues mutually exclusive by, for example, creating two ratios or just leaving highly rated government bond collateral out of scope for the full LR treatment.

Why the SFTR is inefficient

The SFTR’s intended objective is to yield transparency on the following idiosyncratic and systemic issues:

- Term and maturity transformation in SFT markets

- Collateral transformation and facilitation of credit growth, and build-up of leverage

- Interconnectedness of SFT markets

The SFTR is considered inefficient in the Finadium survey even though it has yet to officially go-live. Why is that?

According to a paper by the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), term and maturity transformation in SFT markets is limited (and already captured in a broader context via the LCR).[5] With more than 65% of European repo markets trading government collateral, the amount of collateral transformation (the upgrading of credit collateral) is also relatively low. Eventually, the ESRB paper looks at interconnectedness and the network structure of repo markets. The idea of interconnectedness comes from infection models. If one market participant catches a cold, it would affect all of his trading partners, who, in turn, would spread the disease to their trading partners, eventually giving rise to a chain reaction and subsequent market failure. But on this point, the paper reveals limited interconnectedness in repo markets.

In other words, the SFTR currently fails regarding the first criteria: it does not seem to fill an economic void, and it currently lacks a story on what exactly it should promote or help to achieve. Still, market participants seem to give the SFTR the benefit of the doubt and this does make sense: the SFTR has the potential in the context of a more integrated approach, combining different data gathering exercises within the regulatory spectrum that could add up in a very meaningful way. Market participants seem to feel that the SFTR will eventually find an economic application.

The NSFR does not meet any criteria for efficiency

Market participants give only low scores for efficiency of the NSFR, another instrument in waiting. While an extension of the LCR beyond its one-month realm towards one year does make some sense, it is inconsistent to have both LCR and NSFR overlapping in the one-month area. As the LCR is managed up to three months in advance, the actual economic overlap is even greater. Moreover, both the LCR and NSFR are inconsistent. The NSFR in its current form seems to overrule the LCR, for instance, with regard to open or overnight SFT transactions; the NSFR demands roughly 100% term cash regardless of the quality of the collateral. This is in stark contrast to the more intelligent and collateral weighted treatment of the LCR. According to the Finadium study, more than 50% of market participants cover one-year stable funding requirements beyond 18 months and some even beyond 36 month terms.

With a steeper interest rate curve, the NSFR has the potential to become a primary problem for ultra-short-term and low risk SFT as the high cost of long-term unsecured funds will be channeled into ultra-short-term collateralized markets. This has the potential to seriously impair short-term liquidity of European repo markets. This matters on many levels for improving market functioning, including, according to ECB Executive Board Member Benoît Coeuré, that “the repo market is a cornerstone in the transmission of monetary policy”.[6] This is not the only inconsistency: the asymmetrical treatment of assets and liabilities is again in violation of principles laid out in the LCR but would overrule it. It would make sense to revisit areas of overlap between the LCR and NSFR to ensure greater consistency and create a more efficient tool of regulation.

How to get from efficient to smart regulation

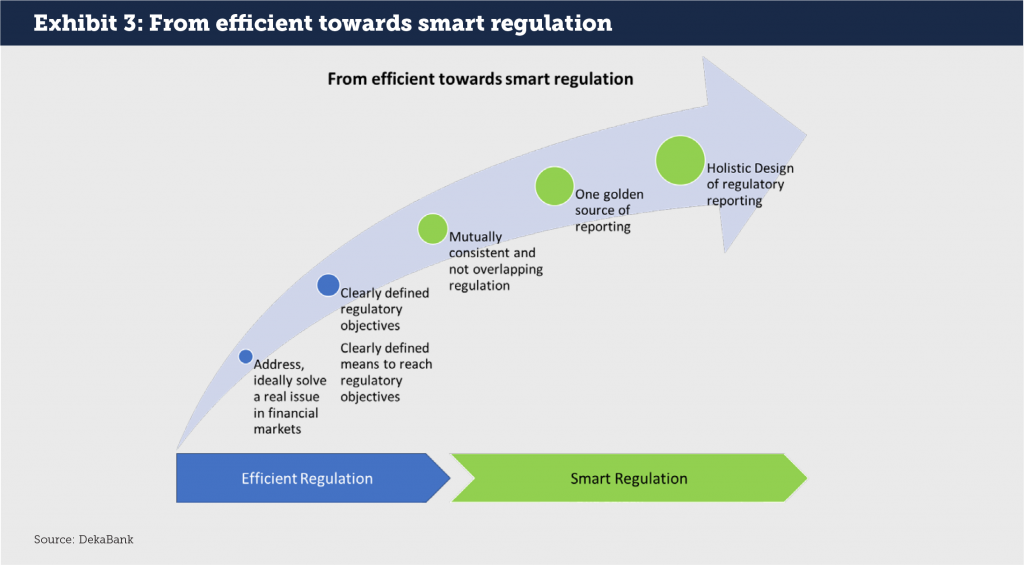

Efficiency can be defined as a feature of a single regulatory measure that addresses an economic need and has a clear objective and clearly defined means to achieve these objectives. Extending this to smart regulation, we can define it as a set of regulatory requirements that minimizes negative externalities between themselves and even gives rise to positive externalities: systemic or emergent features of the financial system as a whole like liquidity, stability, robustness, and sustainability.

The Finadium survey of SFT market participants shows three important points to achieve smart regulation:

Regulatory instruments should be mutually consistent and not overlapping

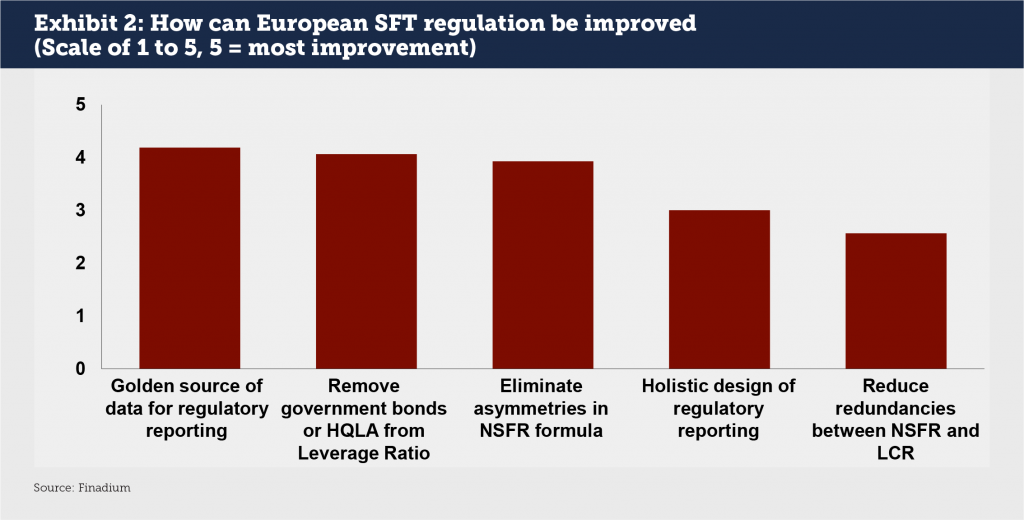

Market participants feel that the establishment of a golden source of regulatory reporting would improve regulation for SFT markets most (see Exhibit 2). I discussed in a recent article that regulatory reporting for money and SFT markets is scattered across a variety of different regulators, which gather similar data in different formats at different time intervals.[7] Meanwhile, mined data sets are in incompatible formats, redundant, or inconsistent in no small part due to the tendency of regulatory bodies to prefer talking vertically to their banking counterparties rather than horizontally to their colleagues from different regulatory bodies. Moreover, communication between banks and regulators is inefficient because one bank talks to different regulators asking for similar, but not the same information. Market participants feel that having one regulatory body (ESMA, ECB, or similar) specializing in collecting, streamlining, and publishing this data would go a long way in improving SFT regulation.

One specialized institution should gather all relevant data. Data should, where it does not violate secrecy laws, be made transparent. There should be a golden source of regulatory reporting.

Market participants raise a further aspect for improving SFT markets: coming up with a holistic design of regulatory reporting. Currently, with all the data gathered, regulators are unable to calculate elementary regulatory or financial key numbers like the LCR, the Leverage Ratio, or the balance sheet just to name a few. This is not only suboptimal, it also raises questions over the intended overall design of different regulatory building blocks.

Regulatory reporting should be holistic. Data items should be gathered in a way that regulators and market participants can approximate key regulatory numbers or key financial ratios on a continuous, near time basis.

This is where regulation should be more ambitious. Many larger banks are already calculating key ratios such as the LCR or LR on a daily basis. These are not audit proof numbers, rather approximations where the impact of balance sheet items that exhibit inertia – like cash flows of loans or some structured assets – are updated on a less frequent basis. More fluid balance sheet items like money, derivatives, or SFTs are updated daily or in some cases even on an intraday basis, especially for bigger transactions that have a significant impact. Combining fluid and non-fluid transactions, one can arrive at a daily approximation of the LCR, LR, liquidity buffers, balance sheet, and other meaningful ratios or key numbers.

Creating one data set that would combine Money Market Statistical Reporting (MMSR), SFTR, EMIR, and the Analytical Data Credit Set (ANACredit), as well as adhere to the principles outlined above, is a distinct possibility. Regulators are already collecting large data pools on a daily basis, for instance, MMSR, SFTR when it goes live, and different EMIR reporting requirements for derivatives. As a corollary, regulators, and certainly the larger banks, should already have between 80% and 90% of the more fluid balance sheet items available. Coupled with ANACredit, they would get monthly information on less fluid loan items. Such a design of regulatory reporting would massively increase transparency for regulators and, if that data would be made publicly available, increase transparency for the market as a whole. This would yield a positive externality that would feed back into macroprudential regulation, monetary policy, and market efficiency. In other words, it would be very smart regulation.

Bringing it together: how to make European (SFT) regulation smart and efficient

We can find six simple criteria for regulatory improvements that would help design regulation that is consistent, efficient, and eventually even smart instead of unduly diminishing real economy growth rates. Exhibit 3 gives an overview of the different criteria outlined in the article.

For such a design, we must ensure that different regulatory measures make sense on their own, fill an economic need, address potential market failures, and increase market resilience. Additionally, regulatory measures must have clear objectives and well-defined means to reach them. Objectives need to be met at minimal cost (it’s worth repeating that cost should be defined in a holistic way) in order to be efficient. Action needs to be taken to ensure that different building blocks of regulation interact smoothly, do not overlap, and are consistent. This is where regulation becomes smart.

Smart regulation acknowledges the need for having one golden source of regulatory reporting instead of fragmented agencies picking up similar or different data items in different frequencies in different formats. A golden source would help streamline communication and coordination between regulators and market participants as well as yield consistent data sets that are neither overlapping nor redundant. Banks have addressed the deficiencies of fragmented / silo organizational structures post-financial crisis by all kind of inter-organizational measures like a strengthened Treasury function, firm-wide and consistent Funds Transfer Pricing, firm-wide centralized funding desks, collateral optimization initiatives, consistent derivatives pricing taking account of liquidity, unsecured risk, and many more. Regulators seem to be trailing behind, but should be able to catch up easily.

Stable and robust markets are characterized by high transparency and low information gathering requirements, especially in times of stress. This could be achieved by aggregating different regulatory cornerstones like MMSR, SFTR, EMIR, and ANACredit in such a way that collected data fields add up and allow for near time replication of balance sheet items and regulatory key ratios / numbers like the LCR, LR and liquidity buffers. Such a design would yield positive externalities from the viewpoint of macroprudential regulation, the efficiency and transparency of the financial market, the capacity for regulators to act on demand (near time), and pricing of concrete transactions, among others.

A holistic design based on the principles laid out here would promote financial market stability, increase resilience of the financial sector, enhance sustainability and counter pro-cyclicality. It would capture any potential build-up of leverage, credit or collateral transformation activities, as well as shed light on term transformation in the financial sector on a continuous basis.

Based on the observed reality of financial market regulation over decades, this may seem like a distant dream. But with many regulators collecting and banks managing key regulatory ratios and numbers on a daily basis, it is certainly the natural and next step in the evolution of competitive financial markets. Such a regulatory design would have the potential of creating a level playing field in Europe that would not be detrimental to real economic growth and would deliver its intended goals at minimum cost. Moreover, it would create a competitive edge and could be a driver of financial innovation by freeing up resources that could be allocated to support real economic growth.

Michael Cyrus is Head of Collateral Trading and FX at DekaBank, including Fixed Income Repo, Securities Lending, Equity Finance, Structured Collateralized Solutions and FX. Prior to this current role, he was Head of Short Term Products at Deka. He joined DekaBank from RBS London, where he was global Co-Head of Short Term Markets and Financing responsible for Repo, Collateralized Funding, FX and Interest Rate Prime and ETD. Before RBS, Michael was Head of Credit Financing and Collateral Trading (CFCT) at Dresdner Bank in London focusing on Emerging Market Repo, Equity Finance, Tri-Party Repo, and synthetic financing in fixed income and credit markets. He started his career at Dresdner Bank in Frankfurt. Michael has a wealth of experience in the short-term money, repo, securities lending and financing markets, as well as in treasury operations. He holds a degree in economics from the University of Hamburg.

References

[1] ”A Financial System that Creates Economic Opportunities – Capital Markets”, US Department of the Treasury, October 2017, avaialble at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/A-Financial-System-Capital-Markets-FINAL-FINAL.pdf

[2] “Trump administration calls for rolling back Obama-era financial regulations,“ Washington Post, October 6, 2017, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/10/06/trump-administration-calls-for-rolling-back-obama-era-financial-regulations

[3] Ibid

[4] “Securitized Banking and the Run on Repo,“ Gary B. Gorton and Andrew Metrick, NBER Working Paper Series, August 2009, Gorton, available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w15223

[5] “Securities financing transactions and the (re)use of collateral in Europe,” European Systemic Risk Board Occasional Paper No. 6/2014, September 2014, available at https://www.esrb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/occasional/20140923_occasional_paper_6.pdf?388f621d04dc86a099633308f3a14ad1

[6] “Asset purchases, financial regulation and repo market activity”, Benoît Coeuré, European Central Bank, November 14, 2017, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2017/html/ecb.sp171114_1.en.html

[7] “The layering of regulatory cost on Securities Financial Transactions,“ Michael Cyrus, Securities Finance Monitor, September 19, 2017, available at http://finadium.com/the-layering-of-regulatory-cost-on-securities-financial-transactions/