The WSJ’s Katy Burne published an article this week on CCPs that are being paid interest on large amounts of cash placed at the Fed. We covered this when the Fed’s proposal was first released in 2013. We didn’t think it was a good idea then and, while we understand the argument, we think it is playing out to the detriment of financial markets. Here’s why.

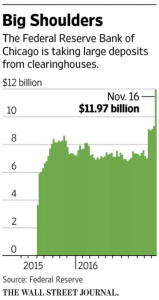

According to the WSJ article, “As of mid-November, units of four major U.S. clearinghouse operators—CME, Depository Trust & Clearing Corp., OCC and Intercontinental Exchange Inc.—had opened accounts worth a combined $20 billion at the Fed, funded with members’ own cash against their trading.” (Exhibit to the right.)

major U.S. clearinghouse operators—CME, Depository Trust & Clearing Corp., OCC and Intercontinental Exchange Inc.—had opened accounts worth a combined $20 billion at the Fed, funded with members’ own cash against their trading.” (Exhibit to the right.)

The argument in favor of this cash going to the Fed is market stability. By getting cash out of the repo market and into the Fed, where it is paid a healthy interest rate, the Fed is removing an element of potential systemic risk from the markets (CCPs invest in bank repo, bank blows up and can’t return cash; or CCPs decide to stop investing in one bank’s repo causing a funding difficulty or crisis). Likewise, the Fed plans to accept cash collateral of end-clients shortly, thanks to an August 2016 exemption by the CFTC. The argument again is that by taking cash out of the hands of dealers and giving it to the Fed, end-users are safer.

Here’s our counterargument in two parts: this is way too expensive for the benefit, and further warps the role of the Central Bank in private markets.

1) Too expensive. While placing cash with the Fed is a good deal for CCPs, the financial terms are a great deal. CCPs currently get paid 50 bps on their cash (the same rate paid from Interest on Excess Reserves, or IOER). Compared to the 25 bps a cash investor gets today from the Fed’s own Reverse Repo Facility, this extra 25 bps is gravy that the CCP can keep or rebate back to its clearing members as an incentive to do business. See Fed rules § 234.7(a) for details on the rate definition for CCPs, which clearly states a long-term investment rate.

Meanwhile, other countries allow CCPs to place cash on the books of the Central Bank but do not pay interest. As we noted in 2013, “This makes it attractive for CCP clearing members in those countries to post cash in negative interest environments but creates no incentive for the CCP itself to keep additional cash at the Central Bank if interest rates are anywhere near positive. Negative rates = CCP good for cash. Positive rates = CCP bad for cash.” Since the US is now in positive rate territory and the Fed is paying interest, CCPs are doing well. Investors looking to place cash (since no one else wants it) will love the Fed’s program too.

The Fed should not be subsidizing CCPs or end-users by paying up for cash left on the books. It has a really good program in place – the Reverse Repo Facility – that pays 25 bps and is becoming more and more a policy tool for keeping rates where the Fed wants them. If anything, leaving cash at the Fed should be a mediocre deal: you get the stability but without the benefit of being paid extra for your cash.

2) The role of public and private markets. The expansion of the Fed’s accounts to hedge funds, pensions and other investors further blurs the line between commercial and Central Banks. Generally speaking, we are against a government entity taking up functions that could be conducted by commercial entities; governments do not have the same incentives to spur economic development forward. Although the efficiency of Central Banks cannot be argued, we find that there is a strong and valuable place in the markets for commercial banks. Unless the Fed wants to be the bank of all banks for CCPs, hedge funds, and any others, then it really doesn’t have a place in accepting their deposits. Paying IOER level rates just adds insult to injury.

We like reducing systemic risk as much as the next group of well-meaning consultants, but the Fed is being overly generous in the process. We know we won’t win the argument on the Fed holding CCP or end-user accounts, and we’ll live with that. But do they really need to be so generous with the rate? Its time to revisit the definition of the rate in section § 234.7(a) for the benefit of the markets and to mitigate potential criticism of the Fed supporting specific market actors over others.

The WSJ article is available here.

Our article is available here.