There has been a lot of press about negative swap rates — where the fixed side of an interest rate swap (IRS) is lower than the equivalent maturity US Treasury. Lower rates imply a better credit counterparty, and in this case better than the US government. But this aberration actually has a repo component that is ignored at one’s peril.

For a swaps dealer to arbitrage the negative spreads, they would have to pay fixed/receive floating in an IRS, buy the US Treasury of the same maturity, then repo the security to finance its purchase. Higher rates on repos and general lack of availability of repo dealer balance sheet makes it more expensive to do the repo trades…and that makes it much harder to lean against the market. So the trade does not get done and the negative spread stays in place. But is this a distortion that will, all things being equal, be arbitraged out eventually? Or once the repo costs are considered, are the markets actually efficient?

A November 23, 2015 article by Tod Skarecky of Clarus Financial Technology “Swap Spreads for Dummies – The LIBOR joke“ has some good observations on the swap spreads and their relationship to repo.

Skarecky set up the following trade:

“…Let’s take the 5 year. The logical play here is to:

- Buy the bond yielding 1.688% at mid (receive 1.688% semi-annually)

- Enter into the swap at 1.578% at mid (pay 1.578% semi-annually)

- This locks in +11bp. Happy days…”

This looks like an easy 11bp profit. But when you add repo to it, there is a problem.

- “…I’d be funding this position at 45 basis points (paying the 3month repo rate every quarter)

- My swap funding leg (receiving LIBOR floating every quarter) most recently (on 20-Nov) settled at ~34 basis points.

- -11 bp gone…”

So the positive spread on the fixed side (=UST yield less swap fixed) disappears when added to the loss on the floating rate side (=LIBOR less repo cost). We should note that the 45bp cost for funding for 3 months is a GC rate. If one assumes the arbitrageur is buying a current 5-year UST, they can probably fund it at a rate substantially less than the 3-month GC rate. But as the bond rolls down the curve, it will become GC soon enough. It also assumes the repo/LIBOR relationship staying the same and constant availability of 3 month term repo financing. Both assumptions are wrong, but we just don’t know how wrong and in which direction.

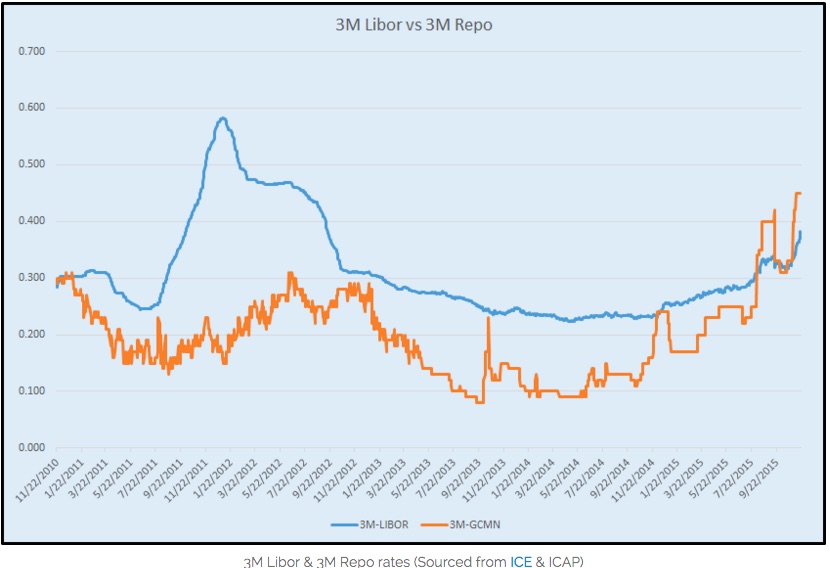

Skarecky also notes that 3 month LIBOR is lower than 3 month GC Repo rates at the moment. Couldn’t a trader simply borrow at LIBOR? Well, if the market participant is not a bank, the answer is pretty much no. And if they were a bank, they would likely get hit with liquidity charges from Treasury to tap unsecured money. He included a great chart:

He also acknowledged he was simplifying the analysis by only including the first 3 months of repo on a 5 year swap, differences in cash flow caused by buying the UST at a discount to par, and the cost to finance IM and VM. But for a back-on-the-envelope analysis, we think this is pretty good.

One lesson from this exercise is swap and repo traders should watch the LIBOR/Repo spreads to give them some clues on how the swap spreads will behave. LIBOR, as an unsecured rate, should be above UST Repo….but as we know, the repo market has a mind of its own these days as it deals with massive regulatory changes.

We are reminded of a Finadium research piece from February 2012 “The Credit Default Swap vs. Repo Trade”. In that report we described how the basis between corporate bond CDS and cash securities blew out during the financial crisis. If an investor could buy bonds and buy protection on that paper and make a profit, it seemed like there was an arbitrage opportunity. Only the trade didn’t have just two parts. The investor had to buy the bond, buy CDS protection, and finance the underlying security. It was the higher haircuts on the repos, higher spreads on the financing, and general lack of availability of leverage that pushed spreads to widen and cause many market players to suffer catastrophic losses.