A June 24th article in the ISDA blog derivatiViews “A MIFID brainteaser: define liquidity” caught our eye. It explains how the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) is thinking about what is liquid and what is not. The blog post is based on a May 22nd ESMA discussion paper on Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) and the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MiFIR). It is interesting to see just how little paper in European markets would be considered liquid. The same is likely true for US markets, especially corporate bonds.

Why does ESMA care? According to the ISDA post:

”…The definition is crucial to much of what is in MIFID and the associated Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MIFIR). Liquid instruments will be subject to strict pre- and post-trade transparency requirements, as well as potentially having to comply with an obligation to trade on a regulated market, multilateral trading facility, organised trading facility or equivalent third-country venue…Under ESMA’s May 22 proposals for post-trade transparency, for instance, information on price, volume and time of trade would have to be made public within five minutes of a transaction in a liquid instrument taking place (although deferrals exist for trades that meet yet-to-be-decided size-specific and large-in-scale thresholds). If an instrument is deemed to be illiquid, however, publication of the most sensitive information is deferred until the end of the following day…”

ESMA is trying to protect market makers in less liquid paper from the world instantaneously finding out that a security traded and at what price. Reporting would not be made public until the end of the following day. This is analogous to the SEF block trading rules and delayed reporting. Except for SEFs the block trading applies to delaying reporting on large trades that might move the market, mitigating the risk of torturing the dealer who provided liquidity and may not have yet hedged or unwound the exposure. In the US there is TRACE, which reports bond trades on investment grade, high yield and convertible corporate debt within 15 minutes of the trade taking place. TRACE has been around for a while (it started in 2002). The near universal push by regulators to provide greater transparency about which securities are trading and at what price seems to take on different twists depending on the underlying market. But we digress.

ESMA looked a 3 primary metrics (from the ESMA report):

i. at least x trades per bond during the period;

ii. the bond is traded on at least x of different days during the period; and

iii. the average daily volume of a bond is at least x EUR (e.g. total turnover over the period divided by the number of trading days).

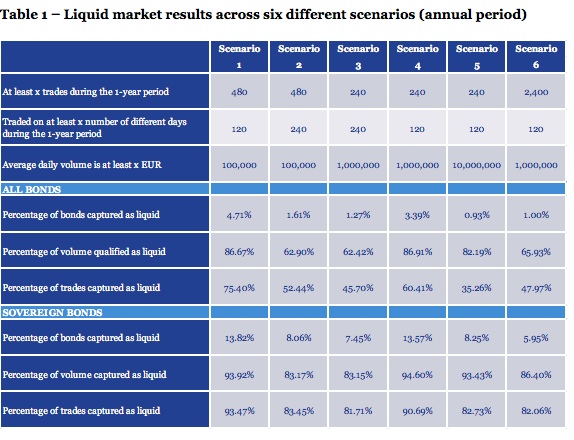

“…Each scenario therefore is based on a different combination of these three criteria which generate a different liquidity threshold. Based on these thresholds ESMA then determined the size of the overall

market – in terms of number of instruments and turnover – deemed to be liquid…”

Not a lot of bonds came out as liquid. 55% of the sample — 40,492 bonds — did not trade at all during the one year examined. Depending on the scenarios — which varied the number of trades over the year, the number of days there were trades, and the average daily volume — the percentage of securities in the sample that could be considered as liquid ranged from 0.93% to 4.71%. The percentage of volume which qualifies as liquid ranged from 62.42% to 86.91%. This tells us that the markets have a small number of bonds which have liquidity, but the vast majority simply don’t trade much.

Source: http://www.esma.europa.eu/system/files/2014-548_discussion_paper_mifid-mifir.pdf

Even so, the ESMA bar was set pretty low. Most of the scenarios looked at paper that trades once or twice a day (240 or 480 times a year). Only one scenario looked at paper that traded 2,400 times a year and that permutation concluded that only 1% of the bonds in the sample would come out as liquid. The primary driver for liquidity, according to ESMA, was how many days during the sample year a bond traded.

These numbers confirm what traders have known for a while. Liquidity in fixed income is highly concentrated in a few bonds (and usually most of the trading takes place shortly after the paper was issued). We expect U.S. markets exhibit the same tendencies, perhaps even more extreme given impact that capital and other regulatory constraints have had on corporate markets. This create a serious vulnerability — the kind the markets saw in the “taper tantrum” last year — to rising interest rates or other shocks. We wrote about that in a post in May “Corporate bond liquidity and new trading venues: will it matter?” Creating more trading venues, which has been the solution de jour, isn’t going to fix this problem. The question remains: how will markets absorb the paper when volatility returns?