A revealing article in the Financial Times last week, “Goldman to sell up to €10bn bonds with new swap,” by Tracy Alloway and Michael Mackenzie, discussed Goldman’s plans to get financing on bond portfolios using Total Return Swaps (TRS). For readers interested in the interplay of financing and traded derivatives (which should be everyone), the story brings up some important market trends.

According to the authors, “The Goldman deal, which the bank is calling a “covered obligation,” uses a TRS provided by a joint venture between the bank and Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance on a changeable portfolio of fixed income assets. Investors also have recourse to Goldman and Sumitomo in a feature typically found in covered bonds – a mainstay of European debt markets.”

Reuters also discussed the bonds on June 27 in “Goldman blurs lines with structured bond” by Helene Durand and Anil Mayre. They note that “The US bank began a roadshow this week for the so-called Fixed Income Global Structured Collateral Obligation (FIGSCO) 2014-01, through Barclays, Credit Agricole, Natixis, UBS and its own investment banking unit. According to S&P, the deal is expected to be a 1bn seven-year trade, from a 10bn programme.” The “Collateral Obligations” are backed “by a portfolio that includes a variety of asset-backed bonds.”

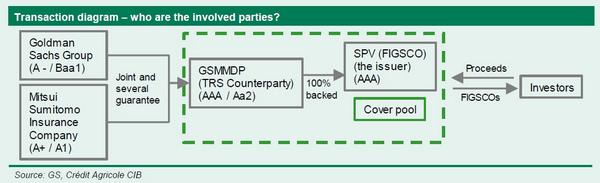

A snapshot from Tracy Alloway’s Twitter feed (seriously, we’re quoting Twitter now? Oh well, got to change with the times) shows the counterparties to the trade:

Let’s break this down: Goldman and Mitsui Sumitomo are offering a rotating portfolio of asset-backed bonds with a defined value as collateral against cash. Hmm, sound familiar? Sounds like ABS repo to us. It also could be read as a proxy for collateralized commercial paper. But hey, if Goldman can finance it for less than 80 bps then its a better deal for the bank even before they look at Basel III capital ratios. Even at 150 bps it might be a better deal especially if costs get passed through to their clients.

Back to the Reuters article: the best part was an off-the-record source that gave up an illustration of the collateral: “An illustrative pool cut shows a 35% exposure to RMBS, 20% consumer ABS, 20% aviation bonds, 0.3% CLOs and 24% unsecured corporate issues, according to sources away from the trade. By currency, the breakdown of the pool might be weighted towards US dollars at 40%, followed by euros with 24%, sterling with 20% and Australian dollars with 15%. By country, the US could account for 30%, followed by the UK and Portugal with 20% each, Australia with 15% and the Gulf with 10%.” The only thing that could make this more attractive would be if the TRS were centrally cleared. Get rid of ABS with a 2% risk weight? We’ll take that.

And investors will take it too. A Bloomberg article from July 25, “Shorting Junk Loans Just Got Easier as New Derivatives Unveiled,” by Lisa Abramowicz, while a little populist for our taste, noted “Total-return swaps on bond indexes are poised to reach about $10 billion this year, mainly focused on high-yield securities,” according to Morgan Stanley.

Meanwhile, Goldman recently said that it had reduced its repo exposure by 25%, from US$100 billion to US$75 billion. The news did not go on to say what else Goldman might be doing to finance assets if anything, but this TRS story provides some important details.

The emergence of this TRS trade is another great example of whack-a-mole: banks need financing and are finding alternative ways to get it. If repo is frowned on, go to the next best thing.

We also note an important idea in the FT article citing Andrew Jackson, chief investment officer at Cairn Capital: ““What’s happened in the past 18 months is people have started to use TRS as a tradable instrument. They can be used as a mechanism to get short or get long – you can go long something that you can’t necessarily buy in the marketplace or go short something that’s difficult to short.” That feeds back into the trend of derivatives as a substitute for the underlying bond particular if liquidity is tight.

We’d say that the plot is thickening, but it isn’t: the plot is obvious. What we’re seeing here is a new operationalization of what needs to happen in financial markets for banks to maintain their business models. Very interesting stuff.