Bank of New York Mellon and the CME have announced a collaboration to produce indices based on tri-party repo and futures contracts on those indices. This was long expected but could also be an uphill battle.

From the CME press release:

“…BNY Mellon’s role in the collaboration will be to prepare and provide daily U.S. Tri-Party Repo Indices that reflect overnight interest rates on Tri-Party Repo transactions collateralized by U.S. Treasuries, Agency Mortgage Backed Securities, and U.S. Agency debt. CME Group futures related to these indices will allow investors to hedge risk on short-term collateralized loans and other nearly risk-free interest rate exposures. The futures products are scheduled to launch in 2015, pending regulatory review, and will be listed by and subject to the rules of the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT)…”

BNY Mellon, with around 85% of the US tri-party clearing market, is in the right position to collect the data. One issue that regulators and market participants have with indices like LIBOR is that they are not based on actual transactions. With the tri-party indices that certainly won’t be the case.

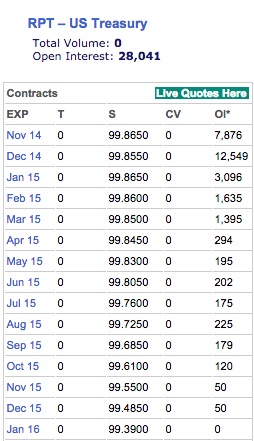

The obvious comparison is to DTCC’s GCF Repo® indices and futures on LIFFE. The DTCC indices are based on actual trades in the inter-dealer GCF market, divided by Treasury, Agency and MBS products. The BNYM indices will have the same product mix. The futures on the DTCC indices have not shown a lot of traction. According to ICE data published on http://repofutures.com/ the open interest and volume numbers are, sadly, pretty anemic.

We wonder what other differences there are between the DTCC indices and LIFFE futures and the BNYM / CME product that would make the BNYM / CME version a greater success. If the difference is simply the use of tri-party data versus DTCC GCF Repo, then it is hard to get excited. GCF Repo(R) has the benefit of being a pure inter-dealer market while tri-party’s participants are much more diffuse.

When we first saw the DTCC GCF / Liffe product, the hope was this could become the de facto short-term interest rate benchmark (see our July 17, 2012 post “GCF Repo Futures have launched”). Replacing Fed Funds, with its low volume and skewed participation, seemed like a good idea. We thought that OIS might change from using Fed Funds effective to overnight repos as the underlying short rate. That’s not happening so fast. Had the US Treasury picked repo as the index for their floating rate note program, it might have been different. Maybe. There is talk on occasion about repo replacing LIBOR as an index for derivatives, but that requires more active long dated trading and curves. Repo would mitigate (much of the) the counterparty credit exposure embedded in LIBOR, but you are still left with the problem of having enough actual trades to validate the numbers. Don’t get us wrong – we think repo is superior to unsecured benchmarks; it is just that outside of overnight repo trading the market liquidity can be, well, episodic.

So who are the natural users of a tri-party futures contract? Money funds could lock in cash investment rates. Dealers could hedge their cost of funds. But frankly none of this feels very different from the GCF futures.

Maybe when short rates become more volatile, the demand for tri-party futures will pick up. The timing of the product might be exactly right.