In 2008, a global de-regulation super trend came to a grinding halt and gave rise to an era of financial repression. However, while financial innovation and financial repression are global phenomena, Europe when compared to the US seems to find it much more difficult to leave the crisis behind and stomach the multitude of regulatory initiatives currently on the table and re-emerge out of crisis, recession and increasing fragmentation.

The Eurozone vs. the US

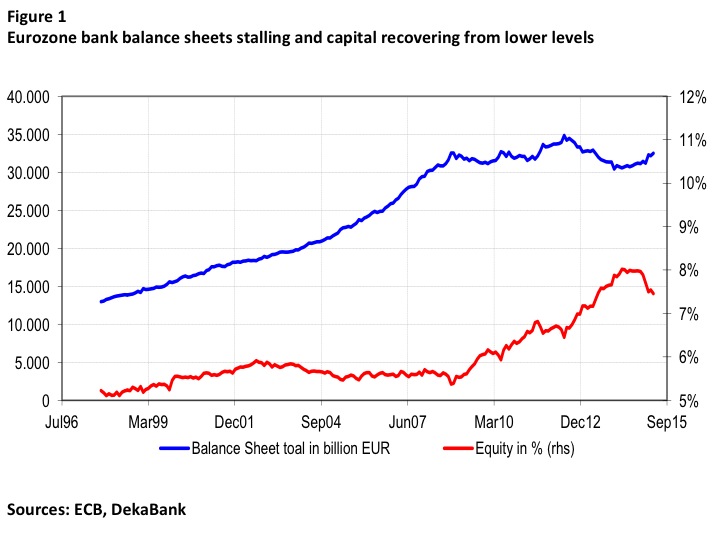

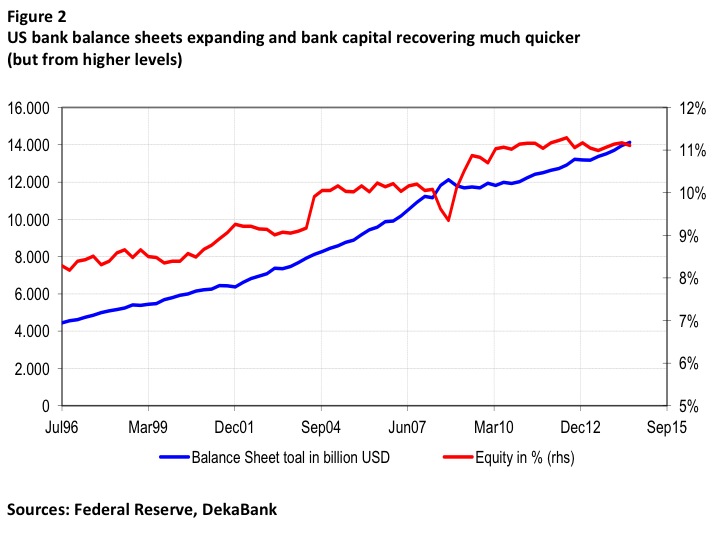

In Europe, regulations seem to have been heavily constraining financial sector growth whereas in the US, where firms were severely impacted, bank balance sheets continued to grow. One primary difference was the starting point of the two banking systems (see Figure 1 and 2). European banks held significantly lower levels of capital and were forced to play a more aggressive game of catch up than US banks to meet new capital requirements. This allowed a certain amount of flexibility in the US that was not apparent in Europe.

Unlike US Banks, European banks did not have any experience with leverage ratios and its introduction caused banks to deleverage more aggressively than their US counterparts. But there were also other important benefits in the US over Europe that had a substantial impact:

- A strong alignment between regulators, the central bank and the Treasury.

- A level playing field for banks and rapid, centralized and coordinated decision-making.

- A culturally homogeneous and centralized market.

- A quick response by US authorities with respect to liquidity programs and a focus on credit instead of highly liquid government bonds.

- A liquidity program accompanied by forced bank recapitalizations.

In the Eurozone on the other hand, there were multiple layers of decision-making but only a loose alignment of authorities. A whole new regulatory structure had to be established first via for example the European Stabilization Mechanism, the Single Resolution Mechanism and the Single Supervisory Authority. The resulting fragmentation and delays in decision making and implementation, jointly with the strictures of the common currency, weakened the fiscal capacity and debt resilience of the individual member countries much more significantly than in the US despite the fact that on average the Eurozone seemed to be on par with the US with respect to public debt metrics.

The crisis rendered obvious that in a single currency area with no fiscal or debt union and limited support structures, the sustainable debt tolerance levels of the constituent member countries are much lower than for an independent country like the US. This is clear from the reaction of capital markets with respect to European peripheral countries where financial markets focused on individual member countries rather than on average Eurozone debt metrics.

The ECB is fighting a lonely game and until recently almost exclusively focused on providing banks with liquidity via long term repos against a wide variety of otherwise difficult to finance instruments. Eventually, it came up with its’ own version of QE. But QE European style focuses mainly on government debt that in Europe profits from a zero risk weight for banks’ capital charges. As such it impacts excess liquidity, interest and exchange rates, stimulating the economy and inflation but providing much less relief for bank balance sheets and their capital positions. What is more, it does not purge bad debt out of the system and thereby fails to address the financial sector problem at its heart.

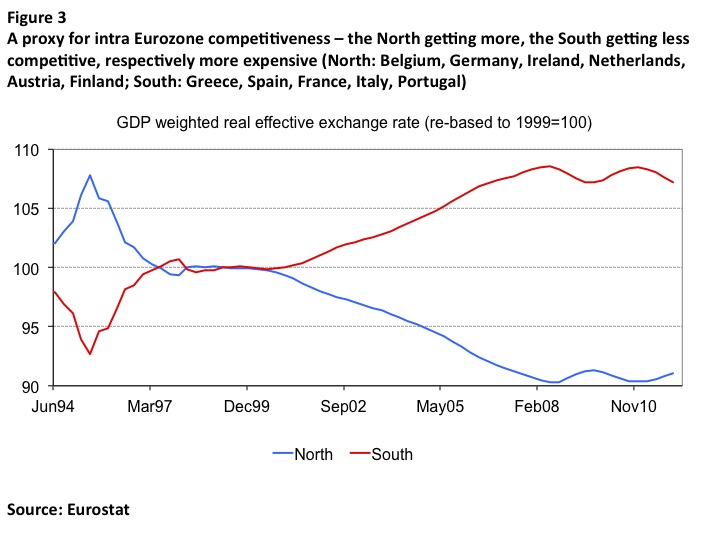

Turning to the real economy, not talking about regional patterns of competitiveness in the Eurozone would be like missing the white elephant in the room. When Europeans established the Euro and got rid of the Bundesbank’s dominance in European interest rate setting, few understood that they substituted the German interest rate setting hegemon with a much more subtle economic adjustment mechanism: unit labor costs. In the Eurozone, unions would have needed to co-ordinate wage negotiations on a pan-Eurozone level and hike wages in line with other member countries and respective productivity growth levels. Instead, southern Europeans continued to set wages according to long established habits, reflecting a high inflation bias, whereas Northern Europeans continued to set their wages according to their low inflation experience. Over the course of a decade, this lack of co-ordination substantially undermined southern European competitiveness (see Figure 3). The financial crisis only accelerated a development that was already long in the making but poorly understood at the time.

For these reasons, any reform agenda needs to balance financial regulation and financial innovation but has the additional task of addressing issues that are profoundly of a European origin.

A European Agenda for Reform

Balancing the needs of regulators who aim at reducing systemic risk on the one hand, versus the needs of the banking sector that wants to secure profitability on the other hand, is a difficult task. An overtly restrictive regulatory regime stifles innovation entirely leading to a banking industry that is unable to put its balance sheet to effective use. This reduces bank profitability as well as economic growth. Moreover, the prospective reduction of bank profitability may not only restrict balance sheet creation but also inadvertently give rise to “zombie” banks. Such “zombie” banks do not have retained earnings and cannot support new business. This is particularly a European issue. Different to the US, Europeans small corporates face small banks that create capital predominantly through retained earnings and not through capital markets. They grant loans rather than marketable debt and equity through capital markets. This is where a large part of the problem lies.

The strong alignment exhibited in the US between the government, the treasury, the central bank and the regulator will remain an elusive goal for the Eurozone. While the banking union is a necessary step in the right direction, the same efficiency as in the US will probably be impossible to achieve. In addition, there will not be any QE US style in the Eurozone. So, what needs to be done in the Eurozone over and above what has been implemented so far? The good news is that the current Eurozone set-up is much better than its reputation, it can work, but only after a certain overhaul. A short to-do list could look like the following:

- Address the bad debt and bad bank problem more radically: The Eurozone will have to clean up the banking system fast. Weak banks need to be recapitalized or closed and the amount of bad debt needs to be reduced significantly so that bank lending channels can be re-opened. Any serious approach in purging bad debt out of the system will have to focus on lower tier, credit and illiquid assets including loans where necessary. These will need to be removed from bank’s balance sheets, potentially in exchange for equity. The current focus on highly liquid, highly rated bonds and term repo operations – while benefitting the broader economy and indirectly helping banks’ balance sheets – does not capture the problem at the root.

- Increase debt resilience on a member country level: Member countries will have to come to grips with the idea that in a monetary union without a fiscal and a debt union, national debt resilience has been reduced. As such, comparing the Eurozone and US debt metrics may overestimate European debt tolerance levels by a large degree. A long-term stable monetary (but not fiscal / debt) union demands further steps to limiting financial imbalances within countries as well as limiting macro-economic divergences between countries. As the current political landscape does not allow the establishment of neither a fiscal nor a debt union, each member country has to work on becoming more resilient against adverse market developments.

For example, Germany recently introduced a debt brake that restricts the amount of public debt communities and Lander entities are able to incur in the future. This was not implemented because Germany has an issue with the current debt levels. It is rather an implicit acknowledgement that in the current imperfect set-up, debt tolerance levels have been greatly reduced, even for Germany. Consequently, more emphasis is being put on strong regional institutions to bring fiscal expenditure and tax capacity in line. As a corollary, any democratic struggle to re-distribute wealth and income going forward will have to be battled out via the tax regime rather than by taking the easy route via issuing more debt, as is often the case in countries with weaker institutional regimes.

- Overcome the North-South (philosophical) divide and implement structural and institutional reforms on a member country level: The Eurozone needs to overcome stereotypical discussions and start making tangible progress on long-term, sustainable institutional reform on a member country level and stop relying on the ECB to always find a last minute fix to a structural problem. The issue is not people in southern Europe being unwilling to work hard enough vs. Germans for the wrong reasons, being inflation haters or determined to dominate the rest of Europe. Lower debt tolerance is an issue for all Eurozone members, not just Southern Europeans; nobody is exempt. The big challenge is to strengthen functioning and vital Eurozone institutions on the one hand e.g. Banking Union, European Stabilization Mechanism, the Single Resolution Mechanism and the Single Supervisory Authority, and accepting and recognizing the inherent (and probably incurable) weaknesses of the Eurozone, like the absence of a debt or fiscal union. Europeans need to accept that these weaknesses are here to stay. And hence, Eurozone participants must set out for more co-ordination with respect to wage setting, debt brakes for entities with limited tax power, tax collection efficiency and similar tolerance levels for corruption and fraud. In essence, the constituent member countries will have to counterbalance the inherent frailty of the Eurozone institutional set-up with much stronger local, communal and regional institutions on a member country level. Deep and thorough institutional and structural reforms based on common values are needed – in some countries more than in others.

Such a reform agenda, with one pillar based on Eurozone institutions and one pillar based on individual member states, would be truly European and will help to save what Europeans traditionally consider to be common achievements based on their value system like free education, affordable health care, unemployment and social benefits, pension systems, jobs for the young, diversity and so much more.

If this agenda is better understood, the crisis offers a chance to fix what had been forgotten in the current framework and work together towards a stronger and more integrated European Union its founders would have envisaged.

Michael Cyrus is Head of Short Term Products at DekaBank.