The second in a series of FRBNY Liberty Street Economics blog posts on programs put in place by the Fed to provide liquidity to the market in response to the funding freeze during the financial crisis has just been published. Entitled “The Fed’s Emergency Liquidity Facilities during the Financial Crisis: The PDCF” by Tobias Adrian and Ernst Schaumburg, it is a good look at one of the most important programs put in place by the Fed: the Primary Dealer Credit Facility.

The discount window had been for years the lender of last resort facility for the U.S. financial system. Banks could borrow against a variety of assets from the Fed, including otherwise illiquid loans, to maintain liquidity. The mere fact that the program was there gave comfort and confidence to those buying bank liabilities. But the securities dealer arms of banks didn’t really look at the discount window in the same way. Internal constraints – systems, accounting, risk, and otherwise — that walled off bank Treasury departments from the securities arms made it torturous to take advantage of the discount window. Non-bank affiliate broker/dealers couldn’t directly tap the window at all. When liquidity dried up in the repo markets during the crisis, the discount window was not going to be up to the task. The Fed created the PDCF to take up the slack.

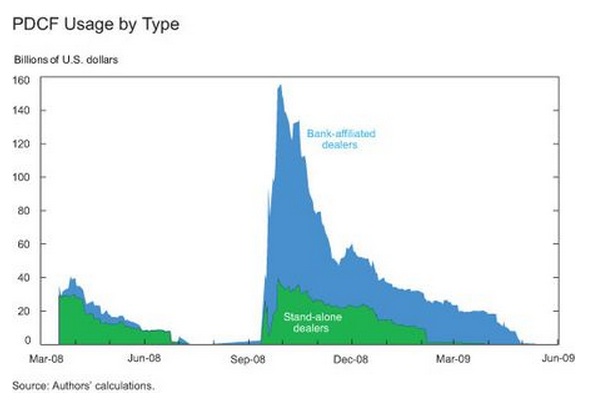

The PDCF was a tri-party repo facility that was incredibly easy to access via existing funding systems. And non-bank primary dealers were eligible to borrow. This aspect of the PDCF was an acknowledgement that the lender of last resort backstop needed to extend past the traditional banks and into the shadow banking world. Non-bank dealers were playing the same kind of maturity transformation function as the banks, albeit with perhaps greater leverage, riskier assets, and no regulatory net underneath. From the post, “…At its peak of $155.8 billion on September 29, 2008, PDCF borrowing was larger than the combined discount window borrowing of all commercial banks. In fact, the PDCF can be viewed as an extension of the Fed’s main lender-of-last-resort facility, the discount window, to the dealer sector…”

Below is a chart from the post illustrating the PDCF usage, dividing the data between banks and stand alone (non-bank) affiliated dealers.

There certainly was a moral hazard problem that came with the program. This came into full view when the Fed expanded the allowable collateral on September 12, 2008. But it was a classic “sharp poke in the eye” dilemma – the alternative was clearly worse. But if the PDCF was the Fed’s carrot, their stick was surely pressure on the biggest of the non-bank affiliated broker/dealers to become banks, with all the regulation that ensues. On September 21, 2008, both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley morphed into bank holding companies.

We said earlier this week in our post on the CPFF, the program designed to provide liquidity to the commercial paper market, “…The Fed acted with great skill when they created the CPFF and, while the counter-factual is always hard to prove, things would have been much worse if they did not have the flexibility to do it. Dodd-Frank takes a lot of that away. While the legislation may achieve the goal of “no more bailouts”, we wonder at what cost?” Ditto for the PDCF.

A link to the blog post is here.