In a recent paper published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), researchers laid out a stylized accounting framework for system-wide debt capacity, when debt serves both as an obligation of the borrower, and also as the collateral pledged by the lender to secure additional funding.

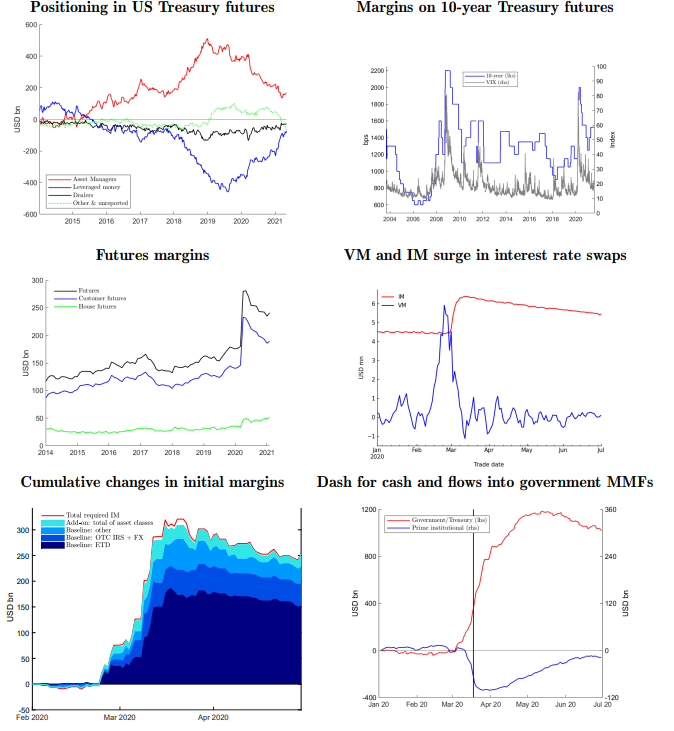

The focus is on fluctuations in margins and leverage. Changes in margin (and the corresponding fluctuations in leverage) are reflected in the fluctuations in the balance sheet size of market participants and in the financial system’s broader risk-taking capacity. A sharp increase in margins, especially after a protracted period of thin margins, will tighten financial conditions for the whole system. Researchers use their framework to provide a perspective on the liquidity imbalances that rocked financial markets in March 2020, amid the uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Over the past decades, non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) have become increasingly central in the supply of credit and liquidity. Collateralized borrowing, such as repurchase agreements, and partially funded exposures, such as centralized or over-the-counter derivatives, are instrumental to the activity of NBFIs.

In both instances, margins determine the debt capacity of intermediaries. For a given amount of capital available, margins are directly linked to the risk that market participants can take and the liquidity they can provide. Researchers found that the recursive nature of debt capacity – namely, that higher leverage by one investor allows others to increase their leverage – magnifies fluctuations in financial activity and generates procyclicality. They also find that sudden reallocation from risky assets to safe havens (dash for cash) is a manifestation of deleveraging.

From a regulatory perspective, the presence of externalities highlights the importance of macroprudential policies. Leaning against procyclicality generated by leverage fluctuations can potentially take the form of minimum initial margins, which would constrain leverage increases and dampen the ensuing declines. Such provisions would complement appropriate self-insurance against adverse shocks, so to minimize the need for leverage adjustments in response to shocks.

In the presence of very large shocks, the public sector – in particular central banks given their flexible balance sheet – may need to provide backstops, thereby supporting debt capacity. Such prospect can alter behaviors and ex-ante incentives to self insure. Hence it is important to make sure that any public backstops be accompanied by an appropriate regulatory framework.