The multi-year bull market in Emerging Markets (EM) debt, and EM corporate fixed income in particular, has been remarkable. The outlook is probably less clear, however, as US interest rate hikes create competition for investor cash, EM fundamentals are less supportive and liquidity in a market downturn is a concerning question mark. A guest article from Natixis.

The multi-year bull market in Emerging Markets (EM) debt, and EM corporate fixed income in particular, has been remarkable. The outlook is probably less clear, however, as US interest rate hikes create competition for investor cash, EM fundamentals are less supportive and liquidity in a market downturn is a concerning question mark. A guest article from Natixis.

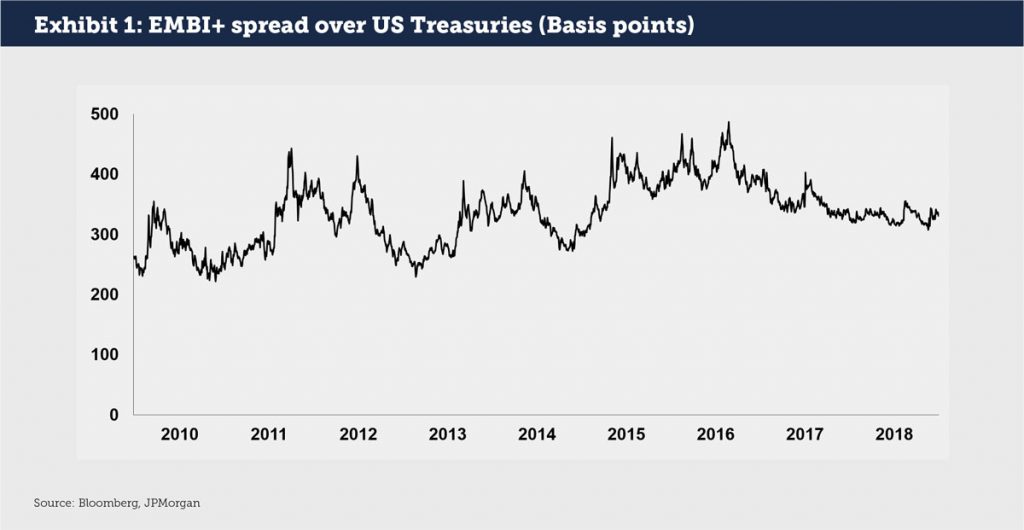

The last eight years have been good for investors holding EM debt instruments. Despite challenging periods (2011, 2013 and from mid-2014 to early 2016), the spread between the J.P. Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index Plus (EMBI+) and US Treasuries has ranged from 222 to 487 basis points, providing substantial profits for risk takers (see Exhibit 1). The EM asset class performance has partly been driven by low US interest rates that have urged investors to look further afield for yield. While US rates have been close or below zero since the 2007-08 crisis, even traditionally conservative investors have been tempted by the kind of yield it was still possible to get in the emerging world, thus attracting a new category of market participants in addition to the EM dedicated players. At the same time, fundamentals in EM countries have dramatically improved since the 90s, the number of issuers (sovereign, financials and corporates) and the size of new issues significantly increased, currencies and tenors are now varied, and liquidity has moved closer to the international standard. Even EM dedicated investors increased their exposures, leading to significant growth in inflows to equity, local and external debt EM funds. EM debt funds posted $76.7 billion of inflows in 2017 compared to $41.6 billion the previous year.

Demand and rates have fueled issuance…

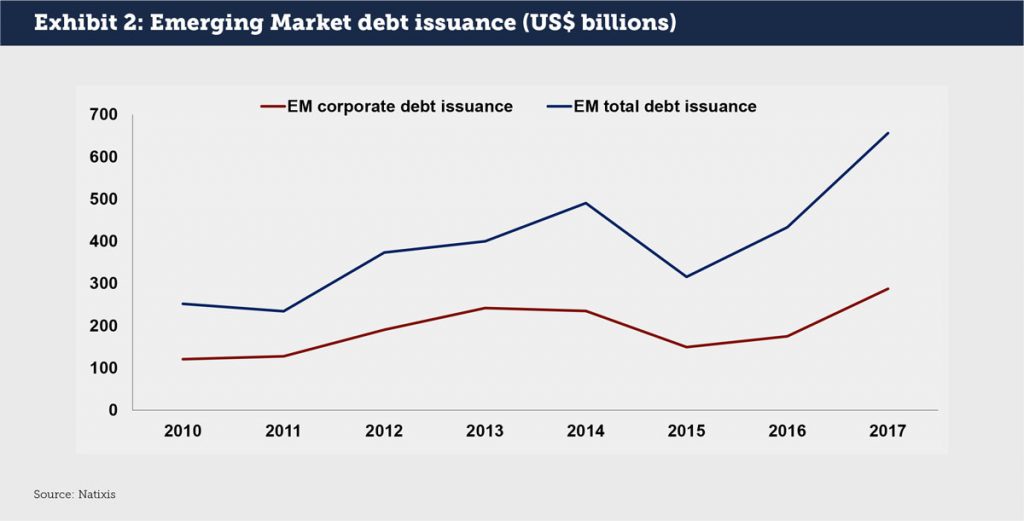

Investor demand for yield products has strongly supported EM issuance in recent years. In a market that has historically been dominated by sovereign issuers, the popularity of EM corporate bonds is noteworthy; EM corporate debt has ranged from 40% to 60% of the total for the last eight years (see Exhibit 2). Backed by a solid sovereign curve that is always used as a benchmark, emerging corporates have been able to tap international capital markets for larger than ever issues over the past few years, meeting demand stimulated by the yield peak up.

And new investment patterns

Traders have described the market for EM debt over the past years as “straight up”. But within this market there have been some significant shifts in how EM debt is held. The prevalence of real money holders and the de-emphasis on leveraged holders such as hedge funds has changed the nature of the market. The buy-and-hold strategy, allowing, in particular, real money taking advantage of yield peak up, has meant less trading of EM debt and then logically an artificially low volatility, especially as far as EM HY corporates are concerned. The spread tightening trend combined with low volatility suited new comers in the EM asset class but there is a question over how possible underperformance of EM debt instruments and a rising volatility would be handled by non-specialist players.Besides, reductions in the ability of bank dealing desks to hold inventory due to Volcker Rule and balance sheet constraints is likely to curb market making and endanger liquidity. The same conditions are evident in US corporate bond trading.

ETFs have also become significant players by broadeningthe availability of EM access beyond the institutional, hedge fund and high net worth market, allowing any market participant looking for exposure an easy way to invest. The top 20 EM fixed income ETFs, as of March 27, 2018, held over $26 billion in assets, according to ETFDB.com (see Exhibit 3). The iShares J.P. Morgan USD Emerging Markets Bond ETF (EMB) had assets of just under $12 billion with a YTD return of -0.64%. Investors have turned to ETFs in EM debt for the same reason as any fixed income asset class: liquidity, convenience and an expectation of consistency in performance relative to an index. At this stage, ETF investors showed greater resilience through market volatility and inflows remain rather strong compared to other types of market participants. However, the behavior of these major players still has to be tested during a sell off that has not yet materialized.

EM debt primary origination desks can point to the last couple years as the best of times. They have seen record new issue volumes and a large number of new issuers meeting ample demand. Amongst the most remarkable issues, we can mention: Postal Savings Bank of China that issued its debut USD-denominated bonds with more than $7 billion in 2017; and Saudi Arabia for the first time tapped international capital markets with a multi-tranche, becoming the biggest EM issue ever in late 2016, and since then, one of the biggest issuers from the Middle East. Natixis has been involved as joint-lead manager in a couple of successful new issues in the emerging world like, euro-denominated Slovakia 30-year, Ivory Coast debut euro-denominated bonds, Egypt USD-denominated 5, 10 and 30-year bonds in 2017, and newly-issued USD-denominated 30-year Senegal in March 2018.

The Fed sneezes, EM catches a cold

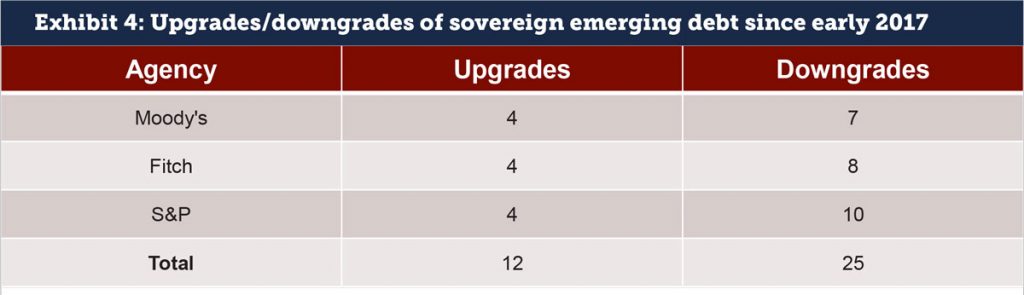

Although the perceived frontiers of EM debt have gotten closer for many institutional investors, leading to greater comfort with the asset class, there are some outstanding concerns. Since early 2017, downgrades on EM sovereign debt have outpaced upgrades more than two to one (see Exhibit 4). Corporate ratings are generally capped at the sovereign ratings, so stress on the sovereign ratings are felt throughout the EM corporate sector.

Globally, the main source of concern in the short term for EM debt is rising US interest rates. The higher US rates rise, the more that competitive pressure for investor cash in low risk securities may cause outflows from the emerging countries, a weakening of emerging currencies and rekindled inflation. In his semi-annual report to the US Congress on February 27, 2018, newly-nominated Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell opened the door for a possible fourth rate hike in 2018, more than the three times expected by the market in response to continued global economic strength, more fiscal stimulation and inflation approaching the Fed’s 2% target. A normalization of the US monetary policy, high US Treasury issuance and poor liquidity bode ill for the EM asset class. While commodity prices are expected to remain strong, Natixis is expecting the depreciation of emerging currencies to remain under control. Consequences of a possible trade war and uncertainties surrounding (re)negotiations of trade agreements with the US are likely to contribute to a growth slowdown in the second half of the year, thus likely capping rate hikes.

Even though the asset class is not at all close to an 80s or 90s style big crisis, the surviving traders from these good old times may still remember troubled moments and they should not be surprised by such a 2018 expected scenario. However, numerous investors not specialized in EM risks, and newly introduced to EM assets, have seen a period of more liquidity and transparency than they may find if unusually low interest rate conditions end. The behavior of this category of market participants will be essential and information extracted from a well-functioning repo market is likely to be a great support in their decision process.

Active over passive for 2018, and a strong repo market will help

Economic and political conditions can vary substantially between countries and regions. Asia, where run ups in leverage on the corporate side have set off alarm bells, will be very different from Latin America or the Middle East. Some countries have not used low interest rates and easy money as an opportunity to strengthen their balance sheets while others have. These differences will play an important role in how EM bonds manage Fed rate hikes over the next year and makes an argument for an active rather than passive approach to EM investing in the short-term.

The efficiency of EM repo desks, and more generally collateralized financing will support moves from passive to active investing, especially if repo desks are able to provide liquidity similar to govies or credit desks. The recently created Global Securities Financing (GSF) activity at Natixis will help to bolster the EM offering to our clients.

Repo helps build bridges between various types of players to match opposite interests. Even on the EM repo market, we now stumble across family offices, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, local banks or Islamic banks (increasingly active through Collateralized Murabaha) in all regions.

The globalization of markets offers opportunities for our clients to capitalize on EM debt around the world. For example, Natixis can provide a cash rich Asian client with some Turkish collateral we have received from a Latin American client who needed financing. Our GSF group can receive a South African Sukuk from a Sovereign Wealth Fund based in the Middle East and lend it to a European HF that needs to cover a short position. Throughout these transactions crossing frontiers, Natixis is fulfilling its fundamental role of financing the global economy at a low cost while meeting its clients’ needs.

The development of an efficient EM repo market is a vital contributor to rich and valuable data, providing market intelligence, and helping market participants reliably value the expected cost and gain of their investments. Natixis views the information that can be collected from a fundamentally bilateral activity like collateralized financing as crucial to further improving the service offered to its clients and to globally better value its investment bank activities.

Remy Tavernier is in charge of Emerging Markets Repo trading within the Global Securities Financing (GSF) group at Natixis. In this capacity, he develops and manages a repo book of non-G7 debt instruments coming from clients in Eastern Europe, Middle East and North Africa, Asia and Latin America. Prior to joining Natixis in 2011 as an EM cash market maker, he was Chief Investment Officer at a Geneva-based hedge fund dedicated to Emerging Fixed Income, FX and Equity and, before, was a proprietary trader at various international banks in London.

Remy Tavernier is in charge of Emerging Markets Repo trading within the Global Securities Financing (GSF) group at Natixis. In this capacity, he develops and manages a repo book of non-G7 debt instruments coming from clients in Eastern Europe, Middle East and North Africa, Asia and Latin America. Prior to joining Natixis in 2011 as an EM cash market maker, he was Chief Investment Officer at a Geneva-based hedge fund dedicated to Emerging Fixed Income, FX and Equity and, before, was a proprietary trader at various international banks in London.

This article has been written in collaboration with Natixis Global Markets Research.