The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) released a report on financial stability implications of support measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The report provides a comprehensive overview of the massive support measures (loan moratoria, public guarantees to loans, public loans, direct grants, tax measures, etc.) that EU governments took and which the ESRB has been collecting information on. It also provides a framework for monitoring financial stability implications of the measures, illustrates some initial results and makes a number of policy suggestions going forward.

Speaking to journalists at a press conference, Claudia Buch, vice president of the Bundesbank and chair of the Working Group which drafted the report, said: “It’s important to avoid cliff effects…to make sure that the measures are maintained for a sufficiently long period of time but not for too long to delay structural change.”

As such, targeting of financial or fiscal measures will now be “crucial” to address solvency issues, she added. In the initial phases of the pandemic, liquidity issues took center stage, however, going forward, Buch called for policy coordination across countries as questions over the timing of any exit strategy loom large.

In terms of monitoring, authorities are paying close attention to debt sustainability of the private sector. Buch said: “The moratoria to some extent delayed the recognition of credit losses and it’s important that this is being monitored. And that also means we need better transparency of bank balance sheets and better reporting so that we understand what the issues are for the banking sector. If we can’t rule out an adverse scenario that means we have to prepare for that to happen so that means we have to make sure there is sufficient capacity to deal with corporate distress and also with workouts of non-performing loans.”

Report highlights:

Although financial stability has been maintained so far, the full effects of the pandemic have yet to show on banks’ balance sheets. A significant volume of bank loans has been extended to some of the hardest-hit sectors in the economy. According to supervisory data, the sectors that are generally most impacted by the measures applied in various countries to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 also had the highest percentages of loans under moratoria.

According to the EBA: “The percentages of loans under moratoria in the hospitality, education and entertainment sectors were significantly higher than the average percentage of loans under moratoria in the NFC (non-financial corporate) segment. In particular, 27% of loans in the accommodation and food service sector were under moratoria, the highest across all sectors. In the education, entertainment, human health services and real estate sectors, as well as in the wholesale and retail trade sector, more than 10% of loans were under moratoria.”

Even though not all these loans will end up as non-performing, banks need to make timely and adequate assessments of credit risk by distinguishing viable but distressed borrowers from unviable borrowers. According to ECB estimates, in a severe but plausible scenario, NPLs in euro area banks could reach €1.4 trillion (roughly 12.9% of total loans), well above the levels seen in the financial and sovereign debt crises.

Granular level data is required for transparency: AnaCredit data can be used to monitor the flow of lending to NFCs on a very granular level. In one analysis, monthly aggregate data from the ECB AnaCredit dataset for euro area countries up to August 2020 were used to explore lending dynamics by NFC size and sector of economic activity, and to consider volume-weighted probabilities of default (PDs) for banks using the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach.

Comparing new commitments to NFCs reported under AnaCredit with the total volume of new loans publicly originated or guaranteed shows the ratio may be as high as one-third. Total uptake of public guarantees and loans for euro area countries amounts to €379.5 billion (as reported by the macroprudential authorities up to September 2020), while cumulative new commitments in AnaCredit for the same set of countries from March to August 2020 amount to €1,082.6 billion. To put the two samples into perspective, these fiscal measures combined account for a sizeable 35% of new commitments reported under AnaCredit.

The challenges banks are facing with regard to credit risk quantification for accounting purposes also apply to the credit risk models they use for prudential purposes such as regulatory capital calculations. The unprecedented circumstances brought about by the global pandemic cannot be adequately captured in existing credit risk models, as these have been calibrated based on historical time series. They have not been calibrated for the unprecedented halt in both supply chains and aggregate demand triggered by the COVID-19 shock; nor has the large-scale deployment of support measures been factored in. Credit risk models may therefore require significant recalibration, depending on the length and permanent consequences of the crisis.

When asked for to elaborate what “significant recalibration” might mean in practice, an ECB spokesperson said: “The need for recalibration will depend on the length and permanent consequences of the crisis. This is mainly the role of banking supervision and in this report we only highlight that this should also be taken into attention.” He also pointed to recent ECB Banking supervision communications on supervisory priorities that include credit risk management.

On the topic of risk weights, the spokesperson pointed to the April 2020 ESRB report, A Review of Macroprudential Policy in the EU in 2019, where the topic of the calibration of models based on historical data was also discussed, namely highlighting that “Even if modeling practices of banks across the EU are compliant with regulatory requirements, they do not necessarily fully incorporate the systemic nature of risks as identified through macroprudential analysis”

An exploratory analysis of the potential financial stability implications of bank failures was also conducted. This suggested that in the absence of policy action and further support measures second-round effects could be material in the event that additional tail risk materialize. Losses on interbank claims could bring about further bank failures, with losses on cross-border claims accounting for a large percentage of these. Contributions by surviving members to deposit guarantee schemes could be an additional source of stress, should these be requested to cover funding gaps.

There could be adverse feedback loops if banks deleverage to meet capital requirements imposed by regulators or markets. The strength of such credit market responses depends, among other factors, on banks’ ability and willingness to use their existing capital buffers to absorb loan losses and maintain lending to households and firms. ECB analysis highlights the importance of banks using them to maintain lending to the real economy, rather than deleveraging to meet regulatory requirements.

An ECB spokesperson noted that so far, funding to the economy continues to flow. In the euro area, a significant part of the new lending to firms has been supported by fiscal measures. Also, some anecdotal evidence has been pointing to the fact that there are still no constraints for the side of supply of lending.

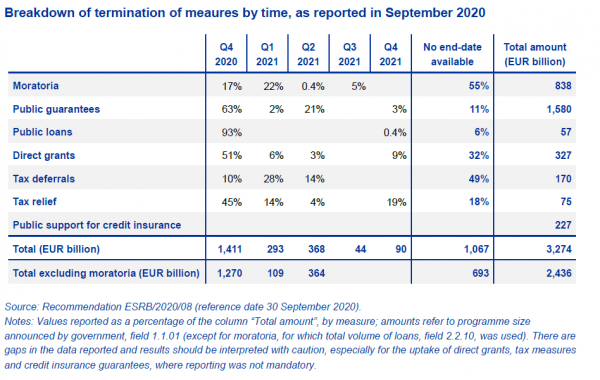

ESRB analysis shows that the bulk of fiscal measures were expected to expire at the end of 2020, but some measures have been extended since member countries last reported. Policymakers are facing a trade-off: if fiscal support is withdrawn prematurely, economic recovery and financial stability might be at risk, but if it is maintained for too long beyond the emergency, fiscal sustainability and longer-term growth may be jeopardized. Managing this trade-off effectively requires timely and reliable information on the state of the economy and the effects of policy measures.

With regard to the impact on the financial sector, the authorities see moratoria and public guarantees as being most important for banks, while direct grants are deemed to be most important for insurance companies and investment funds. Furthermore, most authorities perceive both solvency and liquidity risks as being relatively low across the financial sector. A medium level of risk is highlighted in some jurisdictions, in particular for investment funds. In general, solvency risk is highlighted more frequently for the banking sector.

Authorities are monitoring indicators reflecting the funding, profitability and asset quality of financial institutions to gauge the effects fiscal measures are having on the financial sector. Most authorities highlight the modest effects measures are having on financial sector indicators. Capital adequacy (as measured by CET1 ratio and RWA levels), liquidity (as measured by LCR and NSFR), asset quality (as assessed by growth in NPLs and variations in lending standards on newly issued loans) and lending growth remain broadly stable.

Explanations for this phenomenon vary across authorities. Some attribute it to the high capitalization of the banking sector before the outbreak of COVID-19, which ensured continuous funding to the real economy. Others attribute it to the impact of the fiscal measures taken, which have so far prevented any deterioration in financial stability indicators. Authorities also highlight the heterogeneity of uptake of the different measures. Moratoria are the most common measure, while public guarantees lag behind in terms of application, owing to the unfavorable terms imposed on both borrowers and financial institutions.