Momentum is building toward new plans that could foster greater resiliency in the U.S. Treasury market. The pandemic threw the spotlight back on perceived gaps in the structure of the U.S. Treasury market. Some say the market’s infrastructure, and the Fed’s role in it, needs to change — as perhaps do banking regulations — to foster resiliency. A guest post from BNY Mellon.

Recent stresses in U.S. Treasury trading have been incongruous with a market that holds itself out as the deepest and most liquid in the world. For those trading in March 2020, it was surprising how the pandemic-induced panic threatened the integrity of even safe-haven government securities and how challenging it was to sell them.

Recent stresses in U.S. Treasury trading have been incongruous with a market that holds itself out as the deepest and most liquid in the world. For those trading in March 2020, it was surprising how the pandemic-induced panic threatened the integrity of even safe-haven government securities and how challenging it was to sell them.

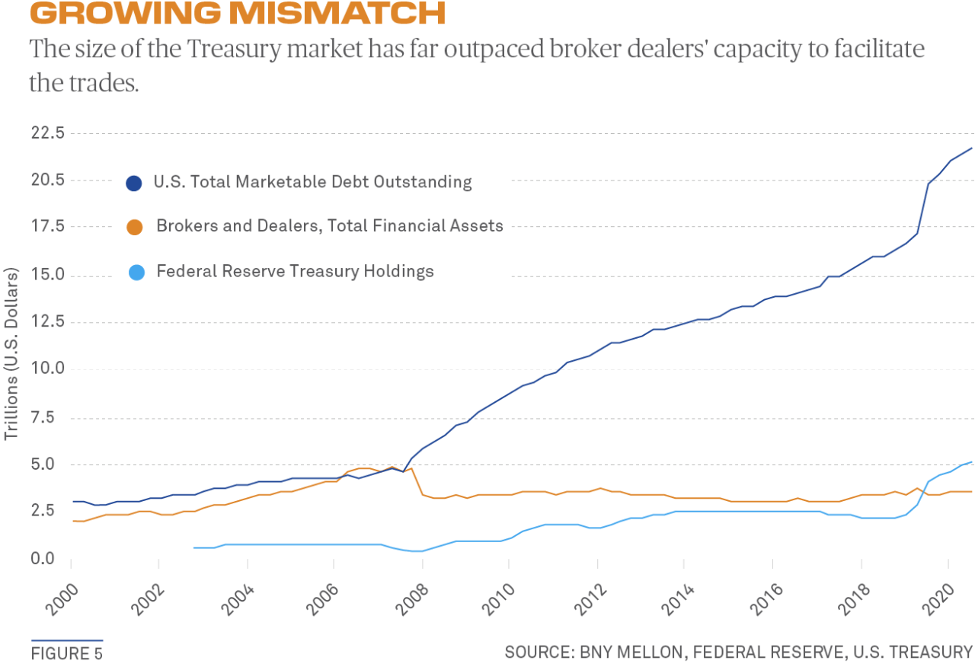

That was just the latest episode exposing fault lines in the $22 trillion Treasury market. Over the years, cracks have emerged as sophisticated technology platforms and high-frequency traders have contributed to faster flows. The size of the market has expanded, overwhelming the capacity of broker dealers to facilitate Treasury trading. And the Federal Reserve has increased its footprint by buying trillions of dollars of Treasuries and shoring up the market for repurchase agreements or “repos” backed by Treasury securities.1

The prevailing view of academics, regulators and others tasked with understanding the latest liquidity shortages is that the Treasury market’s infrastructure, and the Federal Reserve’s role in it, needs to be reevaluated—as do regulations affecting the market. One idea is to broaden access to a new Fed backstop beyond primary dealers and banks. Another is to boost membership of an industry clearinghouse and increase the Fed’s oversight of that utility. A third idea is to revisit leverage rules targeting banks to try to prevent them from gumming up markets and a fourth is to increase transparency.

Some consensus is emerging. The functions underpinning day-to-day Treasury settlements are not a cause for concern. But liquidity is increasingly liable to disappear during periods of stress, which is a worry at a time when the U.S. deficit is growing and when interest rates are expected to rise. Should investors lose faith in their ability to convert Treasuries to cash at reasonable prices, or get the securities they need for hedging, it could have worrisome knock-on effects on securities prices worldwide and potentially the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency.

The industry needs to connect the risks of past events with proposed structural changes that could make the Treasury market more resilient in the future. As an institution that played a pivotal role in the first instance of U.S. government borrowing 200 years ago—and remains one of the principal infrastructure providers in the Treasury market today—BNY Mellon hopes to foster greater stability and better prepare the Treasury market for decades to come.

An Aberration

If market practitioners needed fuel to reignite the long-running debate over issues with the U.S. Treasury market, they found plenty of kindling in March 2020. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, traders sold whatever they could to raise cash.2

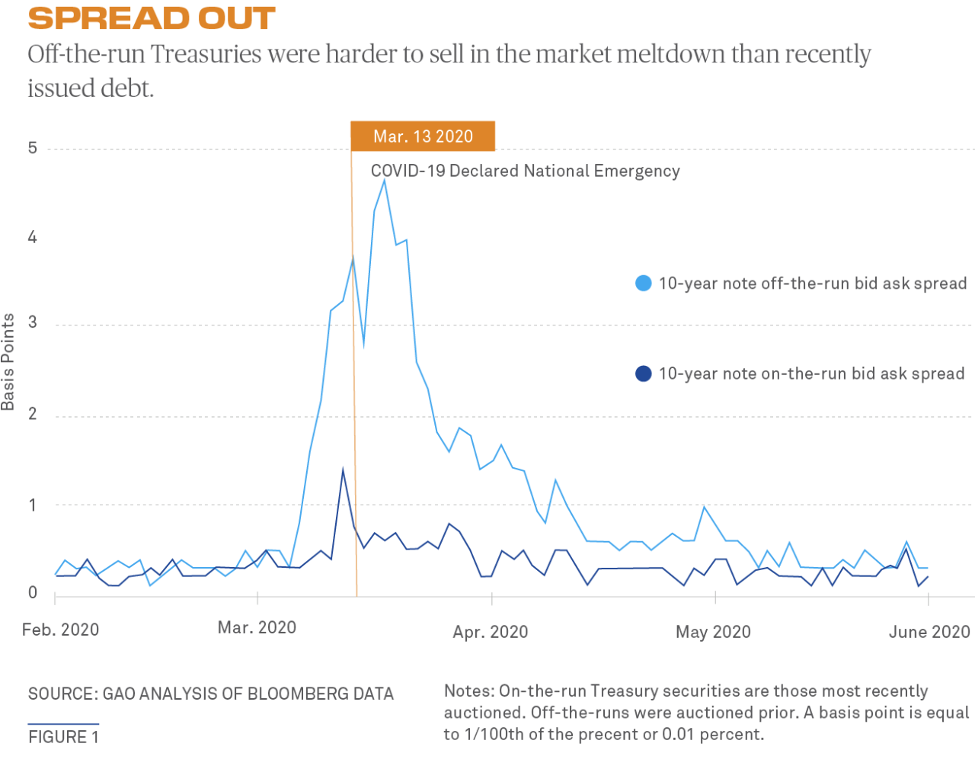

Before the Fed restored calm, it became unusually costly to sell aging “off-the-run” Treasuries in any meaningful size. Between February 26 and March 9, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield fell 80 basis points to 0.55%, or 0.317% intraday, and then rose to 1.20% by March 18—a stark turnaround by historical standards (see Figure 1). Further out on the curve, the difference between where buyers were willing to buy 30-year Treasuries, and sellers sell them, was six times recent norms.3

At times, some traders said it was easier to sell low-grade corporate debt than illiquid Treasuries. “We anticipated that risk assets like credit would see volatility amid a global health and economic crisis,” said Brandon Rasmussen, head of fixed-income trading at Russell Investments, which had $330 billion in assets under management as of June 30, 2021. “It was unusual that the risk-free market experienced a similar period of dislocation.”

Dealers, who often buy and hold bonds on a temporary basis to facilitate client orders, were hamstrung in their ability to make markets because they became sensitive to the size of their balance sheets. Some principal trading firms shut off their automated price-quoting systems, preferring to price transactions manually4—a sign that they preferred human intuition to algorithms during such extreme market moves.

The upheaval relaunched a debate about the Treasury market that began seven years ago, on October 15, 2014, when yields on the 10-year note traded in an abnormally wide range in a window of just 12 minutes.5 The 2015 joint staff report by U.S. government regulators that followed was the biggest review the Treasury market had seen since 1992.6 It covered many of the market’s shortcomings, but few changes were made in the immediate aftermath.

The market for overnight repos has not been immune. In September 2019, rates on those trades spiked to more than 9%7 from previously prevailing levels around 2.3%, prompting a fresh debate about how to foster stability in Treasuries and reduce overreliance on the Fed.

What the market needs now is a package of measures that encourages broker dealers to facilitate secondary market trading using less of their own balance sheets while giving the Fed an option to bypass those middlemen, if needed, and still deliver cash or securities for funding—when and where they are needed. There are complexities to these measures, and some work has already started. But it will take more industry and inter-agency coordination, and time, to achieve meaningful impact.

Calls to address structural problems in the government bond market are coming at a critical juncture. Inflation is taking off just as the Fed is in discussions to reduce the pace of its monthly asset purchases and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are far from over. There is ample room for repeat liquidity crises in Treasuries, with the potential to dent market confidence.

“Eventually it will cost a lot more to finance the U.S. deficit. It would be better to restructure the current market.”

— DARRELL DUFFIE, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

“We are better prepared than we used to be, but we haven’t dealt with the underlying problem,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, senior U.S. rates strategist at TD Securities USA LLC. “Anything can happen tomorrow that’s a Black Swan.”

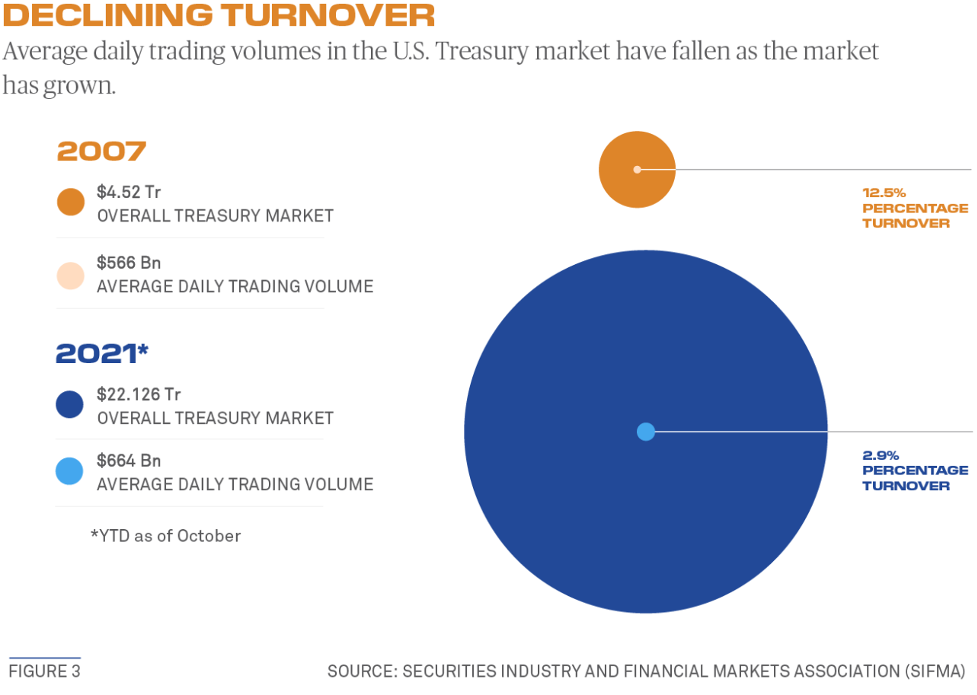

Treasuries are still bought and sold in over-the-counter markets, which are prone to freezing up. As the market has expanded, growing by more than $4 trillion between March 2020 and March 2021 alone, average daily trading has not grown with it (see Figure 3). Investors are also still transacting with other investors through broker dealers, not in “all-to-all” trading venues that are capable of matching anyone with anyone.

“As the crisis in 2020 showed us, access to liquidity needs to be at the top of the market’s agenda,” said Nichola Hunter, head of rates for MarketAxess, a trading platform operator that is planning to extend its existing all-to-all marketplace for credit to Treasuries in the first half of 2022.

For now, the market is helped by high demand for anything perceived to be a high-quality liquid asset and the government is not seen to be at imminent risk of defaulting. But Treasuries cannot continue to be a safe harbor if a large swath of liquidity providers step away when markets get too rocky.

“Eventually it will cost a lot more to finance the U.S. deficit. It would be better to restructure the current market,” said Darrell Duffie, a Stanford University finance professor. A July paper by the Group of Thirty (G30) think tank8 was an initial blueprint of that plan, he added.

Standing Repo and Stigma

This year the Fed made permanent two of the backstops it used to quell the disturbance in early 2020, delivering on one of the pieces of architecture that commentators said was needed in a future stress event. Although that tool is now live, there is still room for enhancement.

The Fed’s “Standing Repo Facility” (SRF) is designed to provide loans at fixed times each day so that firms don’t have to conduct fire sales of Treasuries when they need cash. One of them is a backstop purely for foreign entities,9 which sold nearly $300 billion of Treasuries in March 2020.

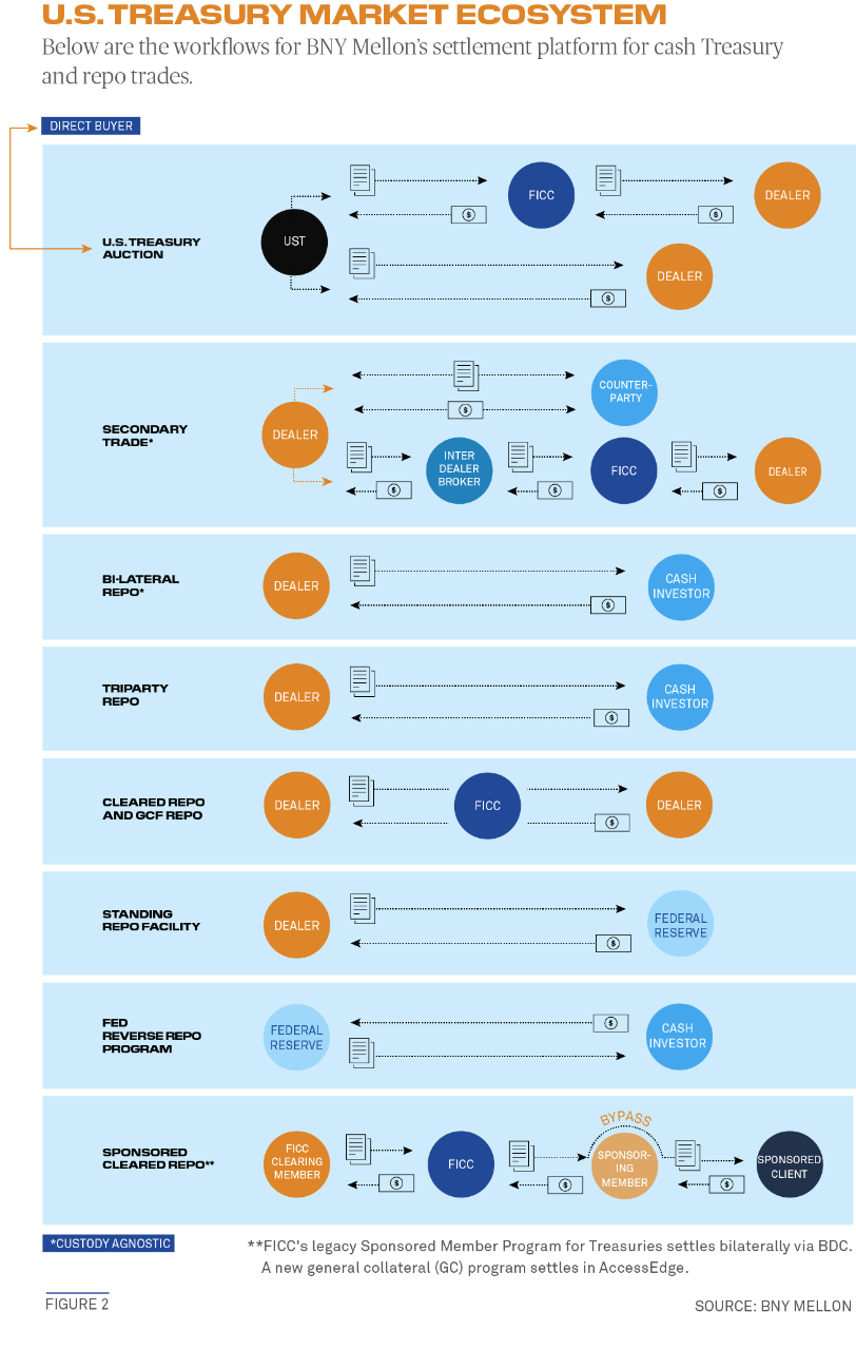

The domestic SRF lends cash to U.S. primary dealers and state or federally chartered commercial banks, with a minimum of $30 billion in assets or $5 billion in securities.10 It settles through a part of the market called “triparty,” leveraging BNY Mellon’s platform (see Figure 2). The loans are available every day at 1.30-1.45p.m.—although some have said the facility should be available on demand—leaving the discount window as the backstop for any late-afternoon funding emergencies.

BNY Mellon has had conversations with 30 prospective banks regarding access to the SRF, said Brian Ruane, CEO of the bank’s Government Securities Services Corp. and Clearance and Collateral Management business. All are early-stage discussions, and it is unclear how many firms will use it even though they meet the access criteria.

Separately, some media outlets have reported that SRF access may not be embedded as part of their liquidity assumptions11 for recovery and resolution planning and stress testing, in which case there could be a stigma attached to using the facility and demand may be muted. The Fed has said it expects to adjust the access criteria for the SRF to allow for a broader set of depository institutions to be counterparties, but no further guidance has been provided.12

Since there can be negative connotations with borrowing from the discount window when the loans are made public,13 the SRF will use auctions instead—and even this may not be enough to negate the stigma. Auctions mean firms can compete for cash and they don’t have to use the facility for last-resort funding emergencies. The daily cap on the facility is set at $500 billion, very close to the maximum amount of Fed support provided in March 2020.

“Some people want to limit the footprint of the Fed, so what this cap is doing is saying it’s only there for a stress event,” said David Andolfatto, senior vice president at the St. Louis Fed. “If such a facility had been made available in the spring of 2020, it would have gone a long way towards quelling the disruption.”

“Our conversations with the PTF community continue, and we are engaging with them to see if there are additional tweaks we can make to clearing to better suit their business model.”

— LAURA KLIMPEL, DTCC

There are calls to see SRF expanded beyond banks and primary dealers, to hedge funds, for example, since it currently falls short of recommendations by the G30 paper. The broader the facility’s access, the less likely the next stress event ricochets around financial markets with dangerous aftershocks. Former New York Fed President William C. Dudley said in a September interview14 with BNY Mellon, “I think it would be better if it was broader—not just opened up to regulated institutions.”

But access to the Fed’s liquidity is only likely to be granted to regulated firms in good standing. Some have warned that expanding usage too far could be problematic if the facility is used too loosely. To prevent it being used in a business-as-usual scenario, the minimum bid rate of 25 basis points is well above standard overnight repo rates. Still, there is a risk that even that rate becomes attractive to lower-tier participants on a regular basis.

Another way for the Fed to broaden its reach with the facility would be having SRF transactions be centrally cleared. This would require the Fed and leveraged investors like hedge funds to get access to the main clearinghouse for Treasuries, which is Fixed Income Clearing Corp. (FICC), a unit of Depository Trust & Clearing Corp.

To add the Fed as a clearinghouse member, FICC would need to find a way to allow the Fed to participate as an exempt member, but “without requiring the Fed to share in potential losses from defaults by FICC members,” said Patrick Parkinson, a special advisor to the Bank Policy Institute and former director of bank supervision at the Fed.

The Fed already leverages BNY Mellon’s triparty and clearing settlement platforms for its open market and monetary policy operations. It also maintains an account at FICC for settling transactions related to U.S. Treasury auctions when the debt is first issued.

In times, the Fed may expand its current borrower requirements for SRF, but currently the central bank has not provided any guidance that it is seeking to become a clearinghouse member or expand its repo facility to leveraged investors.

Clearing is No Panacea

Many commentators say that the market would be safer, and more efficient, if more trades were routed to FICC, although central clearing alone could not resolve problems on days when sellers are selling into a one-way market with insufficient buyers.

A potential clearing mandate would not have to involve all market participants to be beneficial. It could, for example, cover trades through interdealer broker (IDBs), where there is a broker dealer on one side who is clearing, and a principal trading firm on the other who is not.

Currently, most buyers and sellers use a one-to-one process known as “bilateral” settlement, which inserts an agent like BNY Mellon to exchange securities and cash simultaneously on demand. Central clearing is different: one, because the clearinghouse stands in between all participants to buffer their credit risks to one another, manage a potential default and reduce settlement fails; and two, because settlement times are more rigid.

Very few cash Treasury transactions are centrally cleared today, whereas in the derivatives market, roughly 76% of interest-rate swaps are cleared following regulations promulgated by the Dodd Frank financial law. Specifically, more than 75% of cash Treasury trades are uncleared, according to the Treasury Market Practices Group (TMPG),15 and 63% of Treasury repos were uncleared as of Sept. 10, according to the U.S. Office of Financial Research.

Using FICC for clearing offers important benefits but is costly. One is that two opposing trades can be offset and collapsed into a single risk position in a process called “netting”. There are some reasons cash Treasury trades are conducted outside of the clearinghouse. But often the balance sheet relief they can get through netting at FICC allows them to facilitate more Treasury trading.16 Central clearing of cash Treasuries would have lowered dealers’ gross settlement obligations by 60% in early 2020, according to a New York Fed paper.17

One clearinghouse for Treasuries might produce the most netting benefits. Clearing through a single entity also potentially allows the Fed, and FICC, better oversight over a larger swath of the Treasury market.

“Fixing the leverage requirement is probably the biggest thing that can be done.”

— BILL NELSON, BANK POLICY INSTITUTE

Netting at FICC is limited today, however, in part because not everyone is a full-service member of the clearinghouse. There are cross-margining arrangements between Treasury futures trades cleared at the CME Group and cash Treasury trades cleared at FICC, but the companies are proposing to enhance those to improve the model itself and who can benefit from the arrangement—a move that is subject to regulatory approval.

Some researchers have suggested shining a light on the responsibilities of FICC itself. In a July paper by the Futures Industry Association (FIA),18 principal trading firms said there are obstacles to FICC membership and that its margining practices are less than completely transparent.

“Our conversations with the PTF community continue, and we are engaging with them to see if there are additional tweaks we can make to clearing to better suit their business model, including considerations around cross-margining and high frequency trading,” said Laura Klimpel, general manager of FICC.

Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP, said the costs of clearing could be lowered if FICC was able to access funding at the SRF because the availability of a backstop might “reduce the cost of bringing a broader range of trades into central clearing.”

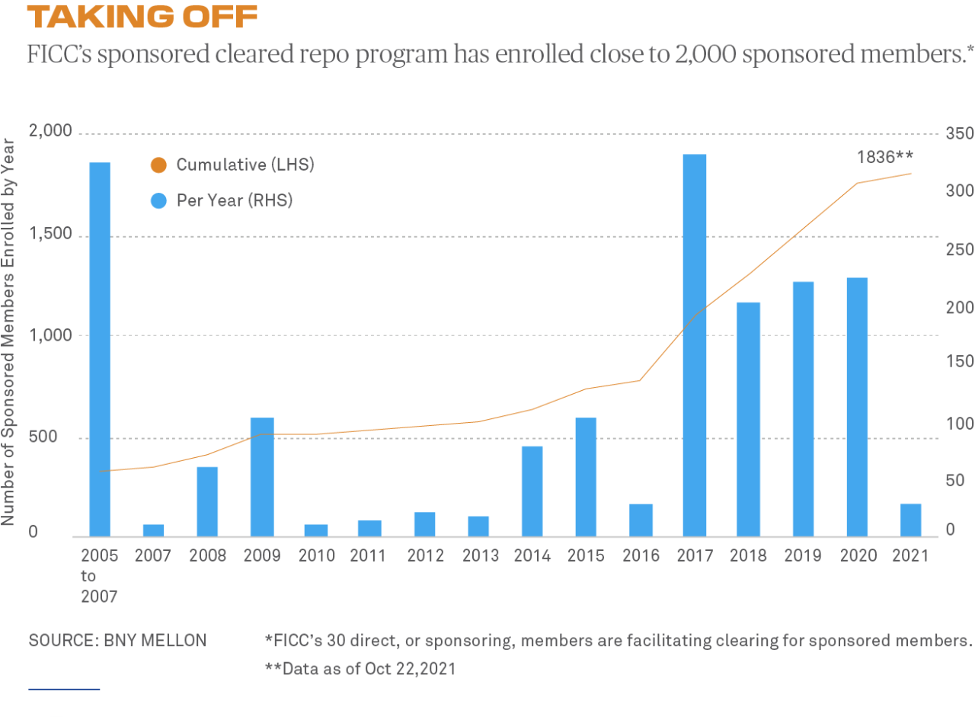

FICC’s most recent efforts have encouraged more overnight repo clearing. The lynchpin of this effort is an arrangement allowing non-members to be sponsored in by FICC members. The counterparties agree their trade details, settle via an agent, and then instruct the agent to pass their trades over to FICC, before the agent steps out of the trade. As of October, there were 30 sponsoring members of FICC cleared repo and almost 2,000 sponsored entities, according to FICC.

Such sponsored repo arrangements actually date back to 2005 but are growing19 because they are helping dealers to continue brokering repos without using their balance sheets while allowing leveraged investors to sidestep the onerous responsibilities of FICC membership. The question is what can be done to encourage more dealers to sponsor Treasury repos into clearing, rather than conducting them bilaterally, as well as how to boost clearing of cash trades.

Another question is one of interagency oversight, given that more activity through FICC is likely. Its main regulator is the Securities and Exchange Commission but since it is designated as a systemically important financial market utility (SIFMU), it is also overseen by the Fed and the Financial Stability Oversight Council. Under Title VIII of Dodd Frank, financial market utility supervision was split between various agencies, so the SEC is the supervisory agency for FICC, but the Fed also has certain supervisory authority.20

Sharing information between regulators should be easy but information-sharing agreements can take a long time. Parkinson said that cooperative oversight involving multiple agencies is a complex process that unavoidably slows the regulatory response to changing circumstances. “Market participants can become frustrated because it’s not clear to them how the interagency decision-making process works,” he said.

An Interagency Working Group for Treasury market surveillance issued a joint report on November 821 saying it was examining recent volatility episodes and potential reforms, including the benefits of expanded central clearing and transparency.

Recalibrating Rules

The most efficient way to fix liquidity in the Treasury market with the biggest payoff may also need to contemplate updates to current banking regulations. The G30, other think tanks and certain public sector officials say those rules are hampering banks’ ability to facilitate trading.

Banks say it is the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) that is impeding their ability to act as middlemen because that rule counts cash and U.S. Treasuries as just as risky as commercial loans. The New York Fed research team has written in the past that, “Regulation may also constrain dealer intermediation activity,” although some banks are no longer SLR constrained.

The Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. briefly changed the SLR in early 2020 to ease strains in the market,22 allowing Treasuries to be exempt from the SLR denominator calculations in the hope it would improve the ability of big dealers to make markets in government bonds. But that relief has since expired.

In March, the Fed said it would invite public comment on “several potential SLR modifications.”23 Meanwhile, academics and policymakers have debated a permanent fix to the leverage ratios, for example by excluding reserves from leverage ratio calculations, and possibly Treasuries, Treasury repos and other borrowings from the Standing Repo Facility under leverage ratio capital calculations.

As written, leverage ratios can be a “binding” capital constraint, meaning that banks must hold the same amount of additional capital whether they are holding super-safe central bank deposits, Treasuries or riskier debt. Former Fed official and current Under Secretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance, Nellie Liang, and Parkinson wrote in a report for the Brookings Institution that reserves at the central bank should be “permanently excluded” from the SLR “because they are riskless” but not Treasuries or Treasury repos because they “have interest rate risk.”24

Other jurisdictions and regulators have adopted their own recalibrations. The U.K. just made the recommendation to raise its SLR from 3% to 3.25%25 while excluding claims on central banks from the leverage ratio.

“BNY Mellon stands ready to support the U.S. Treasury market and our clients—and to help convene further discussions around this important topic… Better liquidity is the route to stability.”

— BRIAN RUANE, BNY MELLON

Fixing leverage ratios is not likely any time soon in part because of the intersection with other banking regulations, the politics of doing so, and the changeover in bank regulators and Fed governors. A fix would also require all three agencies to effect a change at the bank level: the Fed, the OCC and the FDIC.

In a November press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the central bank was looking at “ways we can address liquidity issues through that channel” of SLR regulation.26 No public quantitative impact assessment has been conducted so far, however, and regulators may need to ensure that together, changes to capital rules are capital neutral in the aggregate.

“Fixing the leverage requirement is probably the biggest thing that can be done” along with the psychological benefit of having the SRF to increase confidence in the market, said Bill Nelson, chief economist at the Bank Policy Institute.

Dearth of Data

The fourth pillar in future-proofing the Treasury market may involve more price transparency. Today, government regulators are collecting data on secondary market cash Treasury trades from broker dealers and reporting it to the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), more commonly known as “TRACE.”

None of that cash Treasury trading information is publicly disseminated in real time, so a comprehensive data set is still not available without a delay. It is released weekly as aggregated volume data, for the prior week, going back to January 2019. There is also an incomplete data set on the repo market, because uncleared bilateral trades are still not reported. “There is a thicket of regulations and exemptions that needs to be cleared up,” Duffie notes.

Having a more appropriate level of transparency may be an item on the agenda of the SEC’s new chairman, Gary Gensler. In 2015, then-SEC chair Mary Jo White questioned whether more data should be collected from Treasury trading venues after the October 2014 “flash rally” episode.

In January this year, the Fed invited public comment27 on a proposal to require certain depository institutions to report their Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities trading. There is a delicate balance, however, between introducing sufficient market transparency to meet the expectations of regulators and carving into the already-thin spreads that make facilitating Treasury trading an attractive business. Publicly reported data could incur a small lag so that it supports the overall mission of transparency in being close to real time, but not so instantaneous that it hurts liquidity providers.

Resolving the current blind spot in Treasury data could help the market to assess whether more clearing would make sense. More data around principal trading firms and their algos would also be helpful as trading further migrates from the telephone to the screen; as volatile episodes become more frequent; and as settlement fails become an increasing focus for participants.

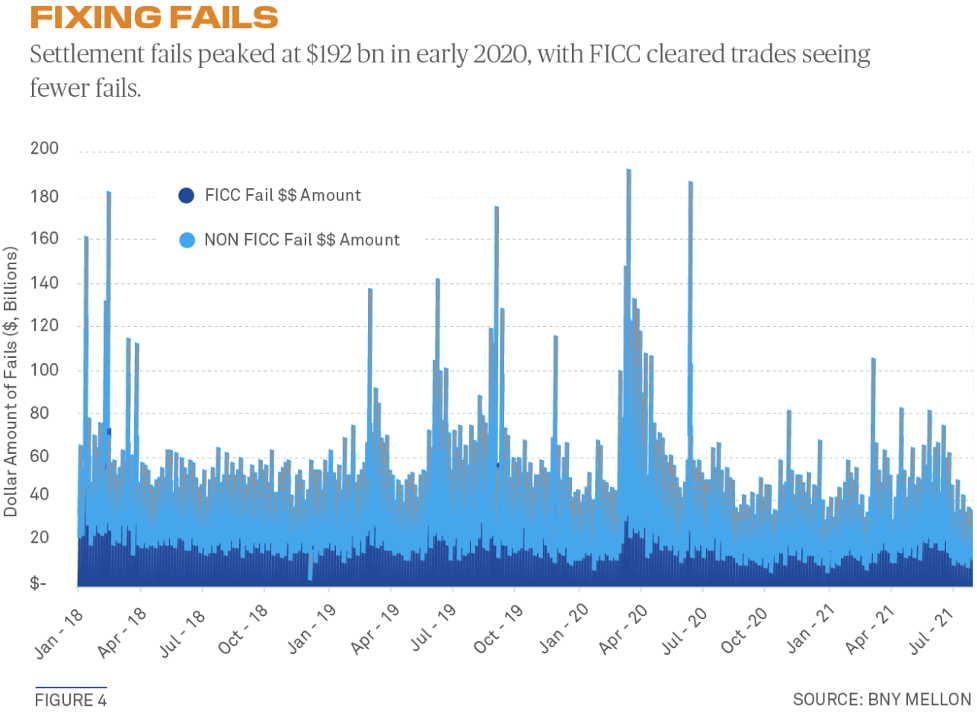

Volumes on FICC almost doubled between March and May 2020, while settlement fails peaked at $192 billion on March 12, 2020 (see Figure 4). BNY Mellon has teamed up with Google Cloud28 to forecast settlement fails hours ahead of the market closing time29—and is now exploring a separate “round robin” pair-off service by itself to reduce fails further.

Restoring Confidence

Whatever the outcome of discussions about perceived flaws in the Treasury market, the recent round of papers suggests there is a need to enhance the market’s liquidity—and some momentum to do so. As it stands, one of the reasons the Treasury market stays healthy in normal times is because Fed operations are so central to its daily function. In extremely abnormal times, the market is not holding up all that well, even with those processes in place (see Figure 5).

Changing the model with more central clearing likely would have had a small positive impact on the stresses of March 2020, but not avoided them. The newly expanded Standing Repo Facility would likely have helped, too. But as each individual measure has a limited impact in isolation, there is a genuine question among some practitioners as to how to move forward—even with the G30 paper as a blueprint.

Some changes, like expanded central clearing, may need to be mandated by regulators. Finding a way for the Fed to interact with the market through FICC, on the other hand, may be the simplest and the most effective immediate change. The challenge will be the coordination efforts of implementing such changes and the time this may take. It remains unclear whether the right sort of package will materialize in time for the next liquidity crisis—especially if there is insufficient regulatory or political will.

With calls for market improvements and no silver bullet, a package of well-thought-out solutions has a higher chance of having a material impact in the next stress event. “BNY Mellon stands ready to support the U.S. Treasury market and our clients—and to help convene further discussions around this important topic,” says Ruane. “Better liquidity is the route to stability.”

Katy Burne is Editor-in-Chief of Aerial View Magazine in New York.

Questions or Comments?

Write to Kevin.Reinert@bnymellon.com in Clearance and Collateral Management; Kieran.Lynch@bnymellon.com for BNY Mellon Markets; or reach out to your usual relationship manager.

See Important Disclosure Information

Footnotes

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WALCL

- https://www.bnymellon.com/us/en/insights/all-insights/the-pandemic-stress-test-us-government-securities-clearance-repo.html

- https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/04/treasury-market-liquidity-during-the-covid-19-crisis/

- https://www.fia.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/FIA-PTG_Paper_Resilient%20Treasury%20Market_FINAL.pdf

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jl0136

- https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Joint_Staff_Report_Treasury_10-15-2015.pdf

- https://www.bnymellon.com/us/en/insights/aerial-view-magazine/deciphering-a-repo-dislocation.html

- https://group30.org/images/uploads/publications/G30_U.S_._Treasury_Markets-_Steps_Toward_Increased_Resilience__1.pdf

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fima-repo-facility-faqs.htm

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/repo-agreement-ops-faq.html

- https://www.risk.net/regulation/7889771/fed-repo-backstop-wont-help-intraday-liquidity-stress

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/opolicy/operating_policy_210831

- https://bpi.com/discount-window-stigma-we-have-met-the-enemy-and-he-is-us/

- https://www.bnymellon.com/us/en/insights/perspectives/preparing-for-the-next-economic-stress-test.html

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/microsites/tmpg/files/TMPG-CS-Outreach.pdf

- https://www.dtcc.com/~/media/Files/Downloads/WhitePapers/FICC-Central-Clearing-WP-Treasury-Market

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr964.pdf

- https://www.fia.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/FIA-PTG_Paper_Resilient%20Treasury%20Market_FINAL.pdf

- https://www.bnymellon.com/us/en/insights/aerial-view-magazine/sponsored-repos-are-surging.html

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/designated_fmu_about.htm

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0470

- https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/05/treasury-market-liquidity-and-the-federal-reserve-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20210319a.htm

- https://www.brookings.edu/research/enhancing-liquidity-of-the-u-s-treasury-market-under-stress/

- https://www.risk.net/risk-quantum/6810371/the-boe-leverage-ratio-welcome-relief-or-regulatory-arbitrage

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20211103.pdf

- https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/21/2021-01217/proposed-agency-information-collection-activities-comment-request

- https://www.bnymellon.com/us/en/about-us/newsroom/company-news/bny-mellon-and-google-cloud-collaborate-to-help-transform-us-treasury-market-settlement-and-clearance-process.html

- https://www.bnymellon.com/us/en/insights/aerial-view-magazine/how-to-succeed-in-fixing-settlement-fails.html