The New York Fed has been on a full court press on the topic of liquidity. Nearly a dozen posts in Liberty Street Economics blog and speeches on the topic have similar underlying themes: regulation is not the culprit and liquidity remains within historical norms. Market participants aren’t buying it.

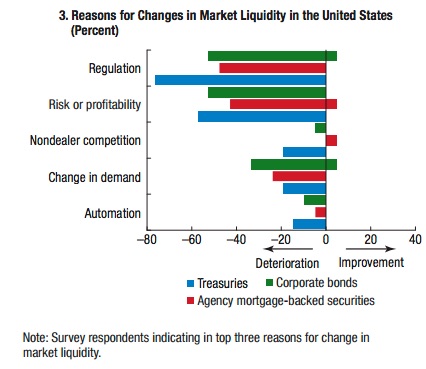

In a survey on what was driving market illiquidity that was cited by the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR): Vulnerabilities, Legacies, and Policy Challenges ,Risks Rotating to Emerging Markets (October 2015), regulation took the top spot followed by risk or profitability. Virtually all of the changes in the markets had caused liquidity to deteriorate. How can there be such a disconnect between the Fed and the market?

Source: IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR): Vulnerabilities, Legacies, and Policy Challenges ,Risks Rotating to Emerging Markets (October 2014)

Source: IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR): Vulnerabilities, Legacies, and Policy Challenges ,Risks Rotating to Emerging Markets (October 2014)

One of last week’s LSE blog installments “Has Liquidity Risk in the Treasury and Equity Markets Increased?” (Oct 6, 2015) put the Fed’s view succinctly:

“…Market analysts frequently argue that regulatory changes since the crisis have led to a deterioration in market liquidity. Their argument is that the new regulations that forced dealers to be better capitalized and to manage risk more prudently have increased the cost of market making. Our findings, however, seem to contradict this potential driver of liquidity risk…”

In the LSE The Liquidity Mirage post (Oct. 9, 2015), the authors suggested that HFT trading had negatively impact liquidity. The HFT argument has appeared frequently from the regulators, especially when explaining anything that has the term “flash” in front of it. Automation showed up near the bottom of the list of the IMF survey.

Other causes include the increased holdings of corporate paper in mutual funds, especially open ended funds. This makes a good deal of sense. An explanation of this appeared in the IMF paper referred to above:

“…larger holdings by mutual funds… are associated with more severe liquidity declines during stress periods…The result is stronger if the measure of ownership concentration focuses on open-end mutual funds, which is consistent with the view that these funds have a more fickle investor base…”

So is there another side of the liquidity argument with evidence to “blame” regulatory changes on the decline in liquidity? Some of it comes from the IMF paper. They are not willing to reject regulatory changes as the culprit — just there hasn’t been enough time to answer the question. The IMF does agree with the Fed that structural changes have impacted liquidity.

“…Reduced market making seems to have had a detrimental impact on the level of market liquidity, but this decline is likely driven by a variety of factors. In other areas, the impact of regulation is clearer. For example, restrictions on derivatives trading (such as those imposed by the European Union in 2012) have weakened the liquidity of the underlying assets…”

The IMF has been a bit more balanced than the Fed when it comes to considering regulation. Here are a couple quotes:

- “…Reductions in market making appear to have harmed market liquidity, and banks now seem to face tighter balance sheet constraints for market making compared with the precrisis period. Nevertheless, conclusive evidence regarding the role of regulation as the driver of this development is still lacking…”

- “…regulations requiring banks to increase capital buffers and restrictions on proprietary trading may have led them to retrench from trading and market-making activities….”

- “…Evidence from the U.S. bond market indicates that when inventories at dealers are low or when dealers’ ability to make markets is impaired, aggregate liquidity is more likely to drop sharply…”

- “…Market liquidity that is low is also likely to be fragile, that is, prone to evaporation in response to shocks…”

While the focus of the analysis is primarily on market liquidity, funding liquidity is important too and cannot be ignored. From the IMF:

“…Funding liquidity, for example, is typically a prerequisite for market liquidity, since market makers also use credit to maintain inventories. Market liquidity, for its part, tends to enhance funding liquidity because margin requirements depend on the ease with which securities can be sold…”

There is little doubt that funding liquidity has been reduced. While regulators might suggest it is because of banks becoming more risk adverse (and lowering institution leverage) alongside the SLA becoming a binding constraint, SFT professionals would counter that HQLA repo isn’t very risky — yet has contracted considerably — and that leverage and capital rules are pushing the businesses to shrink.

The IMF does pull in factors like QE (something we have not often seen the Fed do when analyzing liquidity risks). While QE has reduced liquidity by taking out so many securities, the preponderance of evidence suggests QE and its downstream effects have actually improved liquidity. The downside is that unwinding of QE and liftoff are going to present potentially major liquidity risks.

“…Benign cyclical conditions are masking liquidity risks…many of these cyclical determinants—investor risk appetite, and macroeconomic and monetary policy conditions—are creating very benign market liquidity conditions, but they can turn quickly, and spillovers of weak liquidity across asset classes (including emerging market assets) have increased…”

At the end of the day, the IMF is saying we don’t really know the full impact of regulatory change on market liquidity and liquidity risks. But like the Fed, they emphasize that the regulatory changes have made the financial system safer.

“…Regulatory changes aimed at curbing risk taking by banks can impair their capacity to make markets, but the evidence so far is not sufficient to support revisions to the regulatory reform agenda. Indeed, the reforms have made the core of the financial system safer. The empirical findings of this chapter suggest that constraints on dealers’ balance sheets may impair market liquidity, and that these constraints have become tighter—but it is difficult to link such developments to specific regulatory changes. In particular, not enough time has passed to assess the impact of many Basel III innovations, such as the leverage ratio requirement, the net stable funding ratio, the increase in capital requirements, and restrictions on proprietary trading by banks. Finally, independently of regulations, traditional market makers have also changed their business models by moving from risk warehousing (acting as dealers) to risk distribution (acting as brokers), in part because of technological changes and more efficient balance sheet management…”

The disconnect between what the Fed is saying versus what the market is pushing as the root cause of the decline in market liquidity is unprecedented. The IMF seems to fall somewhere in the middle. Unfortunately, by the time there is ample evidence to prove it one way or another, it may be too late. The reality is, in our opinion, that changes in regulation were necessary to (be in place to) reduce market liquidity, but not sufficient. The interaction of structural changes, monetary policy, and regulation has created a very complex model that is very hard to predict.

1 Comment. Leave new

[…] that liquidity has not entirely left the building (see our posts here, here, here, here, and here), Giancarlo’s speech seemed bombastic. Sure, there were lots of footnotes making reference to […]