When discussing data for regulatory reporting, the European Union currently suffers from a burdensome approach to reporting across multiple and often inconsistent regulations. A golden source of data for regulatory reporting is not just important, it is critical for efficient and “Smart Regulation.” A guest post from DekaBank.

This article reports key findings from the “Fitness Check on Supervisory Reporting”and presents new analysis on reporting and balance sheet holdings. It boosts the argument that both regulators and market participants will benefit from one golden source. It also explains why current data mining doesn’t work and how regulators are slowly recognizing the benefits of one robust data repository. The article makes the argument that high frequency databases would allow for high frequency data analysis of the whole balance sheet without needing to depend on period end dates.

The current state of affairs

The European Commission has a definition for Smart Regulation on its webpage: It “is not about more or less legislation, it is about delivering results in the least burdensome way.” This is a great idea and yet the maxim is not always followed in practice. As I have experienced myself, arguments towards a refinement of regulatory action often meet stiff resistance. This is unnecessary however; smart regulation fully accepts the idea that financial markets need to be regulated.

Currently however, similar data points for regulatory reporting are collected into several different repositories, and the same instruments are calculated using similar but not the same methodologies and frequencies depending on whether they are computed for regulatory capital or calculation of the leverage ratio for example. This is often aggravated by the fact that there is a high amount of manual processing, arising from different interpretations and definitions across reporting frameworks.

The shadows of different reporting requirements

Regulatory fragmentation at the national and supranational levels in Europe complicates regulatory reporting. For instance, with respect to MiFIR, banks have to report to national authorities, but for EMIR and SFTR banks must report into EU-wide transaction registers. Data mining is not helpful: 99% of relevant information about equity capital results from only 8% of all data points, according to the EU. There are also data discrepancies between regulatory balance sheet versus financial reporting, which make direct data comparison difficult at best and impossible at worst. (For instance, regulatory reporting uses EZB FX fixing rates, while balance sheet / financial reporting usually uses end of day market FX rates.)

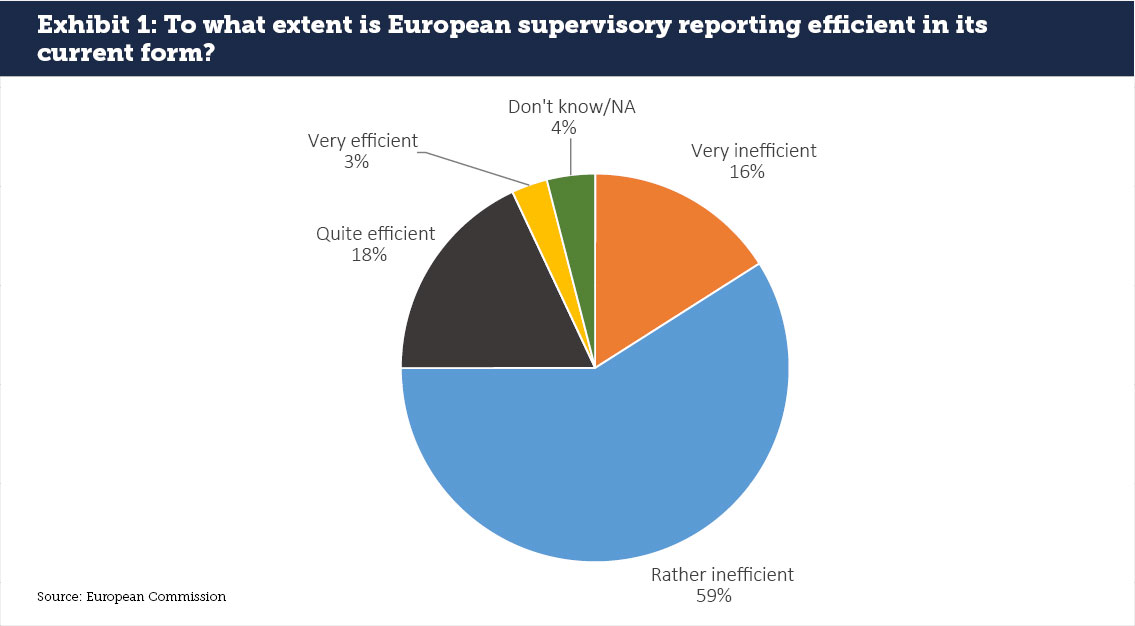

Little wonder then that 75% of respondents to the “Public Consultation on the Fitness Check on Supervisory Reporting” say that the current supervisory mechanism is very or rather inefficient (see Exhibit 1). The 3% that find the regulation to be very efficient are mainly public authorities.

Many smaller and non-complex financial institutions in particular feel that European financial reporting violates its’own definition of smart regulation. They face excessive costs due to the absence of proportionality that should exempt them from certain reporting requirements given their limited impact on systemic stability. European reporting mechanisms for Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), AnaCredit, MiFID and EMIR have either no thresholds or thresholds that require input even where systemic risks are low; the cost of putting together the required data is very high relative to the insights generated. These rules are also out of alignment with other regulatory frameworks like Solvency II, which allow regulators some degree of flexibility in obliging smaller firms to respond.

The opportunity: embedding existing aggregated assets by real time data repositories

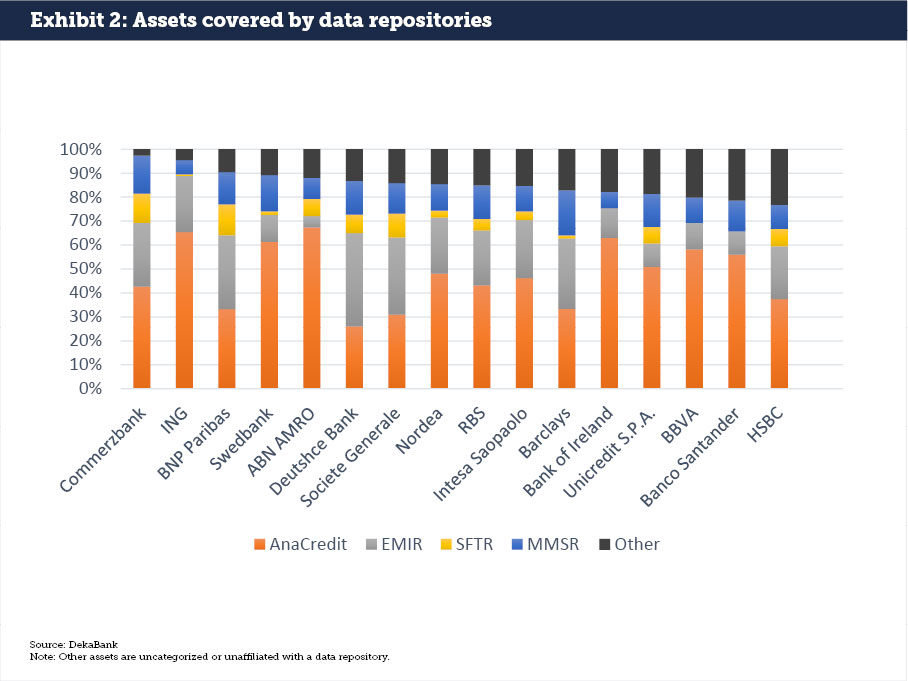

At least in theory, regulatory reporting is already where it should be, given that current regulatory data repositories like Money Market Statistical Reporting (MMSR), AnaCredit, SFTR, EMIR, MiFID/ MiFIR and CRR cover the majority of balance sheets of the largest financial institutions in Europe. We conducted an analysis of 16 representative European GSIBs and DSIBs (global and domestic systemically important banks), and found that more than 85% of balance sheet items on the asset side are covered by these data repositories (see Exhibit 2).

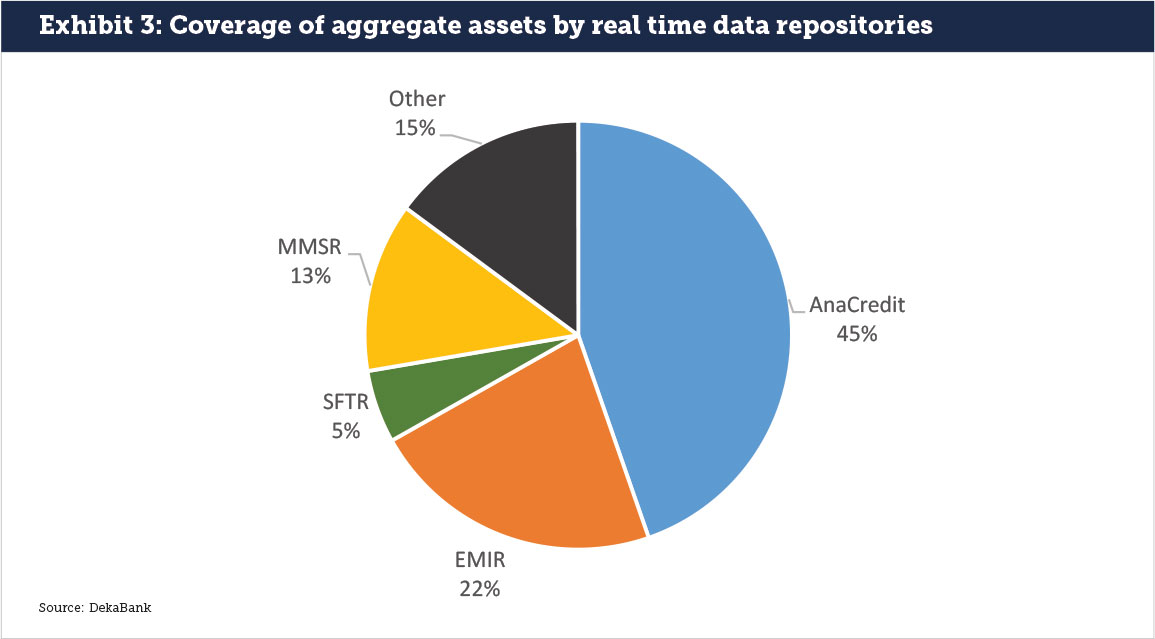

Unsurprisingly, and consistent with the banking structure of Europe, nearly half of the assets of the respective DSIBs and GSIBs are loan assets covered by ANA Credit, followed by EMIR and MMSR assets (see Exhibit 3). Reverse repos and other exposure covered through the new SFTR only make up around 5% of the assets in question. Securities lending activity will only come into play after the introduction of the SFTR but would stay outside a balance sheet item focused analysis as it is off balance sheet. There are obvious limitations in an exercise like this; the disclosure in the published accounts doesn’t match up very well to the SFTR/MMSR universe, and it’s likely that the coverage of EMIR data is not precisely the same as the trading portfolio disclosures in accounts.

In our data analysis, the five main assumptions have been:

- All securities portfolios held for trading (but not other securities portfolios, even if held at fair value) are EMIR / MiFID / MiFIR

- All replacement value of derivatives are also in EMIR

- SFTR assets are directly identified as repo or securities lending

- MMSR is identified as an interbank deposit or central bank item (but not double-counted with repo)

- Customer loans are all AnaCredit

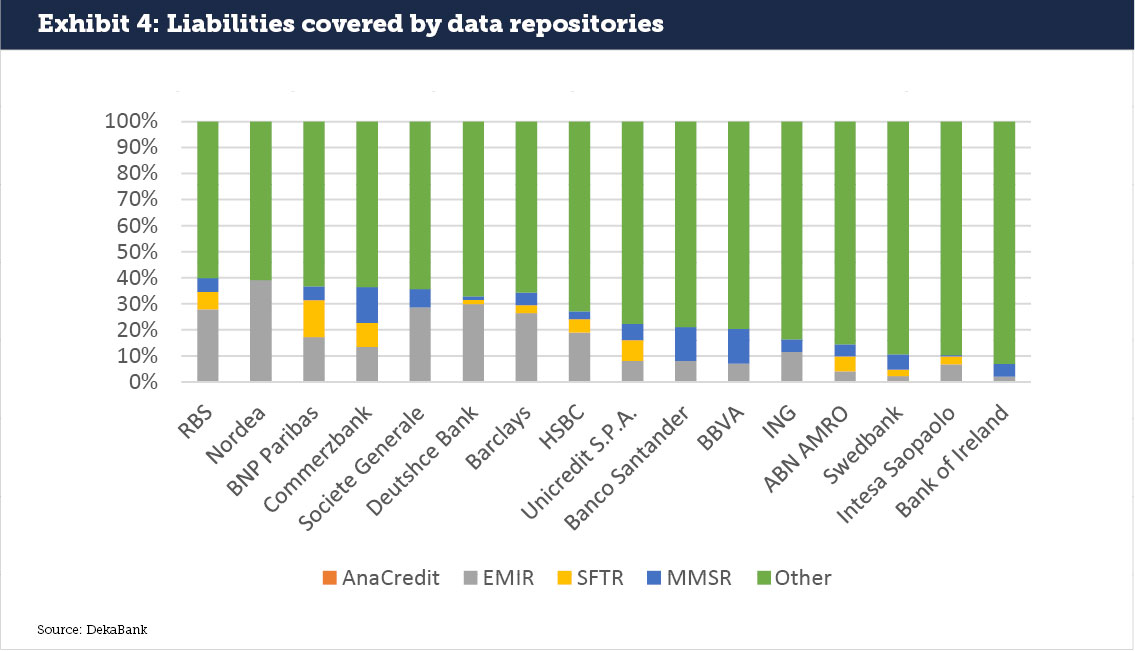

For the asset side of the balance sheet, this strikes a reasonable balance. There will be some items (loans to non-EU customers carried out through non-EU subsidiaries) that are overcounted, but a) there are probably larger amounts of securities holdings that we have conservatively left out even though they are captured by MiFID / MiFIR reporting, and b) the extension of AnaCredit to cover these items is not a particularly difficult task. On the liability side of the balance sheet, the numbers are much lower (see Exhibit 4). Partly, this can be attributed to capital being reported under the CRR, which we did not analyse in this study. But in general, it is much more difficult to link the liability side to the generic definitions of the different regulatory repositories. Hence, the actual coverage might be higher.

Mining existing data repositories doesn’t work

With such vast amounts of financial data being mined and some financial institutions reporting more than 90% of their respective balance sheet items into data repositories in a regular daily, monthly or quarterly format, the idea must be that regulators have gained enormous insights into what banks do between official reporting dates. Unfortunately, while the quantity and in some cases also the quality of data has improved, I strongly doubt regulators can approximate the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, Leverage Ratio, Net Stable Funding Ratio or other simple regulatory ratios from the data being mined.

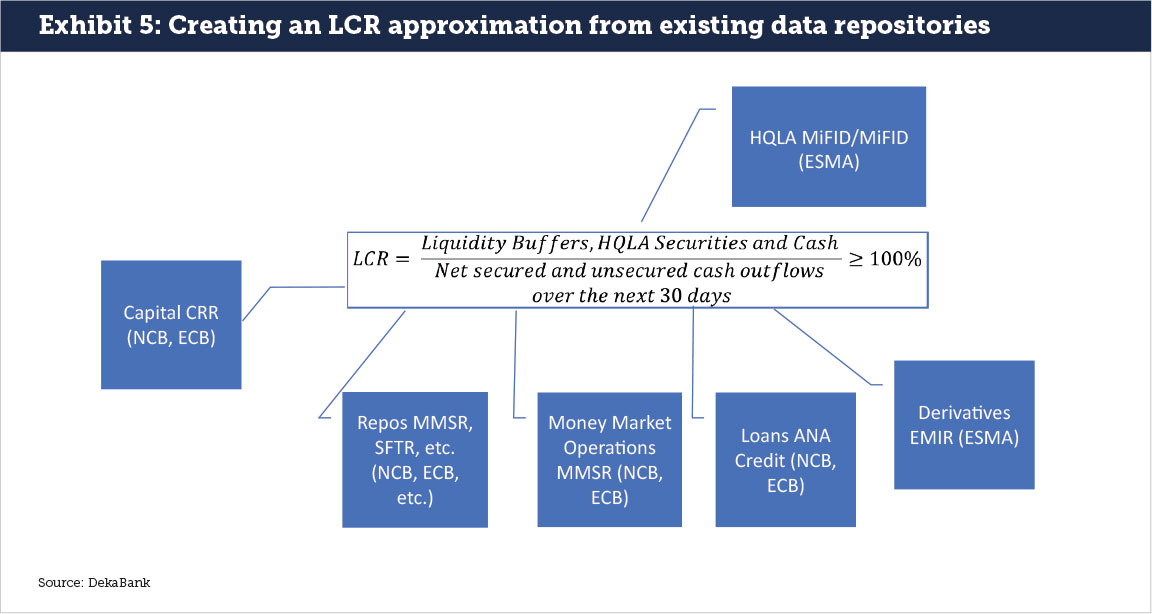

These sobering facts are aggravated as most regulatory ratios need input from all the above-mentioned data repositories. As just one example of many, the LCR needs input from the CRR, EMIR, MMSR, SFTR, AnaCredit, MiFID / MiFIR, and probably additional data repositories. Securities lending markets, which have evolved to support HQLA trading in a significant way and have become quite important for LCR management in many banks, will only enter data repositories with the introduction of the SFTR.

Unlike regulators, many banks approximate key regulatory numbers daily. They have bridged the different product silos, and central regulatory departments are amalgamating data delivery from all kind of legal jurisdictions, departments and product lines in a consistent, non-overlapping and non-redundant way. They have completed their restructuring work since 2007-2008 and in the aftermath of the European government debt crisis of 2010. Regulatory reporting departments ensure that data is enriched where needed and, in some instances, this task is being outsourced to external product providers. Banks are spearheading golden source systems that bifurcate the data into the fragmented regulatory world.

Four key examples of structural change that led to a much-improved overview of liquidity, credit, capital and balance sheet risks include:

- The development of XVA methodologies to gather a better overview of liquidity, funding, capital and credit risk aspects across derivatives departments.

- Collateral optimization across products, departments and legal entities.

- Strengthening, and in some parts centralization, of treasury functions and regulatory reporting departments.

- Creating golden source systems and reducing the overall number of existing systems.

This process of overcoming siloes is good for banks but unfortunately not helping regulators in their data collection efforts. External providers will just help banks to bifurcate data into the different data repositories as required by regulators. But once the data is split into different repositories, regulators will find it difficult to aggregate them back, because European regulators lack central instances, definitions, rule-sets or methodologies for re-aggregation.

For regulators to create a reliable LCR approximation, they would have to bridge all the different data repositories on a near time basis (see Exhibit 5). This is painful enough given the current set up, and it can be safely assumed that regulators still find it much easier to make an ad-hoc phone call, ad-hoc data request or even do an outright onsite inspection to understand the liquidity position of any given bank between official reporting dates than create a robust methodology for data set integration. However, any kind of ad-hoc action will not help make regulatory reporting more efficient.

There is a light at the end of the tunnel, if you take the right train

Regulators are currently trailing behind. They hit the market with an out of date data repository design that resembles the pre-crisis modus operandi. Part of this is understandable, as regulators have continued to manage the “ad-hocery”needed to fix a complex system that was on the brink of disintegration. Consequently though, today’s regulatory reporting set-up is neither cost efficient nor does it meet the European Commission’s idea of Smart Regulation. Moreover, the data being mined does not improve transparency as much as it could because the data in the different repositories is not usable for the calculation of key regulatory ratios.

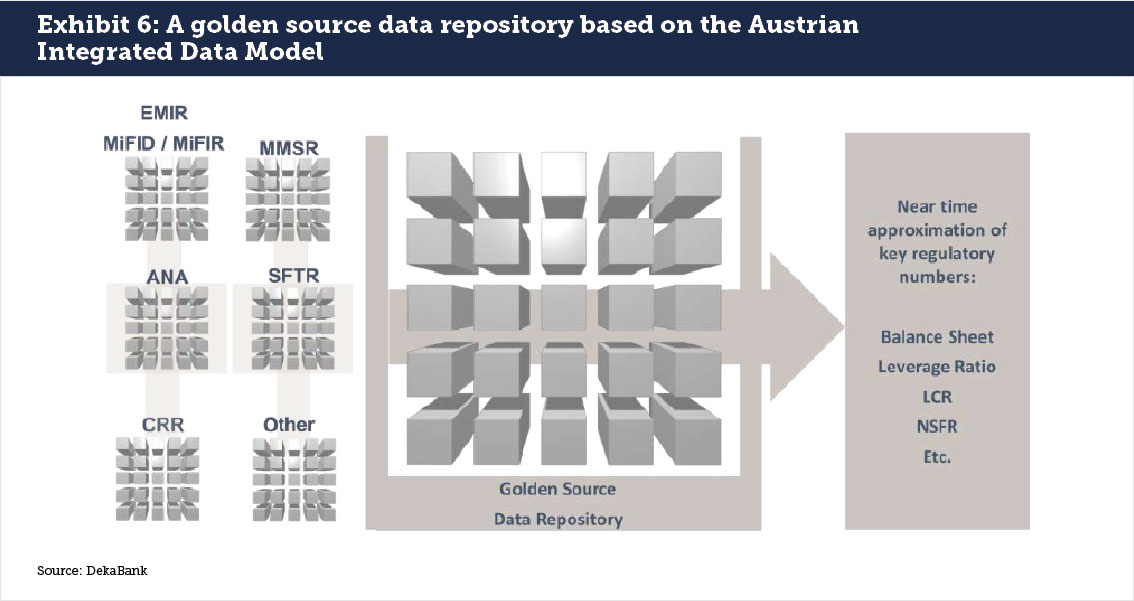

However, there are signs that regulators and banks are starting to enhance the use of existing data and methodologies. One example is the Austrian Integrated Data model. Although it would just apply for AnaCredit, the idea is that regulators will be able to calculate key regulatory ratios from the data they receive without having to go back to the banks. This is certainly a step in the right direction, especially if the model involves no ad-hoc alterations or spot checks to supplement the data.

The Austrian Integrated Data Model should be considered a template for what is achievable (see Exhibit 6). It would address issues like unclear and vague requirements, reporting to multiple data repositories, lack of interoperability, overlapping and inconsistent requirements, lack of a common financial language, insufficient use of international standards and all kind of other issues mentioned in the fitness report.

The bigger challenges for Europe will stem from the fact that most relevant regulatory statistics must bridge not one but many data repositories. The natural solution is one golden source data repository that regulators can draw on for every reporting requirement.While a long way off, this ultimate goal must be developed now in order to reach both a golden source of data and valuable reality of Smart Regulation. It can be done but requires the right vision to move forward.

Michael Cyrus is Head of Collateral Trading and FX at DekaBank, including Fixed Income Repo, Securities Lending, Equity Finance, Structured Collateralized Solutions and FX. Prior to this current role, he was Head of Short Term Products at Deka. He joined DekaBank from RBS London, where he was global Co-Head of Short Term Markets and Financing responsible for Repo, Collateralized Funding, FX, Interest Rate Prime and ETD. Before RBS, Michael was Head of Credit Financing and Collateral Trading (CFCT) at Dresdner Bank in London focusing on Emerging Market Repo, Equity Finance, Tri-Party Repo, and synthetic financing in fixed income and credit markets. Michael has substantial experience in the short-term money, repo, securities lending and financing markets, as well as in treasury operations.

Michael Cyrus is Head of Collateral Trading and FX at DekaBank, including Fixed Income Repo, Securities Lending, Equity Finance, Structured Collateralized Solutions and FX. Prior to this current role, he was Head of Short Term Products at Deka. He joined DekaBank from RBS London, where he was global Co-Head of Short Term Markets and Financing responsible for Repo, Collateralized Funding, FX, Interest Rate Prime and ETD. Before RBS, Michael was Head of Credit Financing and Collateral Trading (CFCT) at Dresdner Bank in London focusing on Emerging Market Repo, Equity Finance, Tri-Party Repo, and synthetic financing in fixed income and credit markets. Michael has substantial experience in the short-term money, repo, securities lending and financing markets, as well as in treasury operations.