It’s time to rethink some long-held assumptions in financial markets. Continuously rising US Treasury issuance will have its natural consequences: it’s not possible for funding markets to take on a limitless amount of capacity. What would happen in practical terms if, when and how that capacity is reached?

![]() This content requires a Finadium subscription. Articles with an unlocked symbol can be accessed with free registration. Log in or create a free account by signing up here..

This content requires a Finadium subscription. Articles with an unlocked symbol can be accessed with free registration. Log in or create a free account by signing up here..

The US Treasury plans to issue another $814 billion in the coming months. A portion of this will be bought by long-term savers and some by carry traders, but another chunk will stay on the balance sheets of primary dealers. Primary dealers are obligated to buy these securities – that’s what it means to be a primary dealer – and we’ve already seen increasing repo volumes as dealers look to finance this inventory.

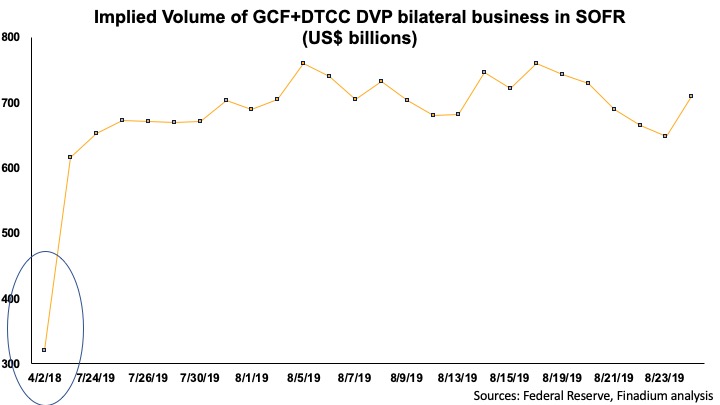

We took the volume spread from the Federal Reserve’s tri-party index vs. SOFR to see what the amount of financing (as defined by the SOFR methodology) has been in GCF Repo(R) and DTCC DVP business. While the data from July and August look pretty stable, around $700 billion, going back to April 2018 we can see that financing volumes have more than doubled (a 121% increase).

Meanwhile, US Treasury issuance has increased from $14.8 trillion in April 2018 to nearly $16 trillion at the end of July 2019. There is no one-to-one ratio of a percentage increase in US dealer financing needs. Rather, we think there is a cliff scenario – everyone who needs funding can get funded, up until a point when the next incremental amount of funding is unavailable.

We’ve seen short-lived versions of this scenario before in US funding markets, for example at the end of December 2018 where average GC rates were over 5% and individual market participants saw rates of over 7%. At the time, while unpleasant for some, it was well recognized that rates would come down quickly after the new year. There was no generalized panic about long-term consequences of a one or two day rate spike. Further, the capacity was there, just at a price.

The new scenario that we present here is that rates rise substantially, stay there, and that volumes would not be able to increase because dealers would have no more capacity to fund. In this case, not all firms that needed funding could get it. This could spark a combination of outcomes, including defaults (probably by smaller dealers reliant on match book financing on GCF) and a sell off in Treasuries by holders unable to finance or unable to finance at a reasonable price point for the trade.

The technical reason for why limits could occur is that primary dealers, forced to take on increasing amounts of US Treasuries, could find their Leverage Ratios ballooning to the point where the total assets (part of the denominator of the ratio) would push their compliance limits. We think first about J.P. Morgan, the largest bank holder of US Treasuries, and Bank of America and Wells Fargo are right up there too. With no alternatives, this could be a market stopping event, including for the ability of the US Treasury to continue issuance at all. Could some big banks opt to no longer be primary dealers? That would be drastic but we have to keep the possibility in scope. If that were to happen, it would put excess pressure on the remaining primary dealers to take on my inventory. No wonder the US Treasury would prefer that USTs not be included in the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (see the US Treasury’s Banking Report from June 2017, page 54).

We can see a number of escape valves to help the market let off funding pressure before a crisis would occur. Smaller dealers could see the opportunity ahead of them and find the resources to increase their funding capacity to other firms. Rates of course will rise, pushing the actual cost of funding through the market to clients, with subsequent impacts on pricing for underlying assets. Maybe these would be tolerable enough to increase funding capacity. Futures products could take up slack, and dealers are already targeting CCPs for repo as a means of expanding their balance sheet capacity. We expect that an actual funding limit for the market as a whole would go through multiple iterations of letting off steam before a limit was actually hit. We don’t see an issue occurring in 2019, but mid-2020 could be another story.