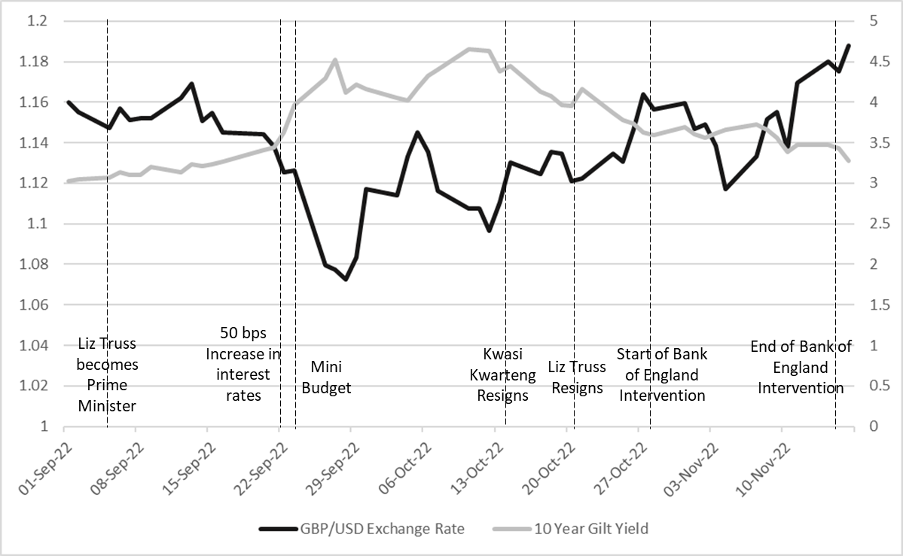

On the 23rd of September 2022, the newly appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer (UK Finance Minister) Kwasi Kwarteng announced a mini budget including £45 Billion of unfunded tax cuts. The reaction from markets to the changes was dramatic: the pound tumbled from $1.12 to under $1.04 by the following Monday and yields on 10-year UK gilts rose by 66 basis points as the price of UK government bonds fell (see Exhibit 1). Though the Bank of England intervened in the gilts market in order to stabilise bond yields and sterling, the crisis ultimately led to the resignation of both Chancellor Kwarteng and the Prime Minister.

Exhibit 1 – Financial Impact of 2022 Mini-Budget

Sources: Yahoo Finance, Bank of England

The immediate trigger of the crisis in gilt and foreign exchange markets really started on the 22nd of September 2022. The Bank of England announced that it would increase base rates by 50bps and reduce its holdings of gilts by £80 billion. Both actions put pressure on gilt prices. Higher interest rates meant gilt yields had to rise to provide returns consistent with bank deposits, which in turn meant bond prices had to fall. The prospect of an additional £80 billion worth of gilts on the market also put downward pressure on the price of gilts. The announcement the next day by the Chancellor of £45 Billion of unfunded tax cuts plunged markets into chaos. Major unfunded tax cuts were expected to increase inflationary pressures in an economy already struggling with a sudden surge of inflation. With the Bank of England having legal independence and an obligation to control inflation, the budget raised the prospect of even more dramatic increases in interest rates and falls in gilt values.

Though the causes of the crisis were clear, the reasons for the dramatic size of bond movements were initially less so. The reasons for the fragility went back many years and in hindsight were not so surprising, except to the government. The origins can be traced back to the 1980s and 1990s with a series of taxation and regulatory changes, many of which were based on good intentions. Up until the 1980s the majority of UK pension schemes provided Defined Benefits (DB) to pensioners. Firms and public sector organisations promised pensions based on the final salary of the pensioner. Often pensions increased in line with inflation. For employees that stayed in the same job for most of their career, a DB pension was a glorious thing. However, changes in 1988 to taxation of dividends received by pension funds and the looting of his company’s pension fund by media baron Robert Maxwell led to a series of changes that meant it was ultimately both unattractive and uneconomic for organisations to offer their staff pensions based on their final salaries. According to actuarial firm Lane Clark & Peacock (LCP), in 1993 “virtually all” FTSE 100 companies offered a membership of defined benefit pensions to new employees. By 2018 none of them did.

Pensions and Liability Driven Investment

The 1990s and early 2000s saw the closure of most DB pensions to new members. The outstanding liabilities were vast: “In 2021, the assets of these funds amounted to £761 billion (30% of the overall assets of UK pension funds).” (Walker 2023) The organisations providing DB pensions looked for a way to be rid of the risks, costs and liabilities on their balance sheet of the remaining DB pensions. The answer provided by the fund management industry was Liability Driven Investment (LDI).

The basic principles of LDI are simple and attractive to both firms and pension regulators. Putting sufficient assets of the right kind into a pension fund so the value of those assets (factoring in future cash flows) is approximately equal to the present value of future payments to pensioners. A fund applying basic LDI principles would:

- Calculate assumed future payments to pensioners based on actuarial projections of future life expectancy and estimations of the final salary for those members of the scheme that have not yet retired.

- Apply a discount rate to the future payments based on the value of the fixed income investments of the fund to calculate the present value of those liabilities. If pension funds have future liabilities linked to the inflation rate, the present value of future liabilities would be discounted by the inflation rate.

- Purchase assets where the future fixed liabilities match the future payments on those securities. If there are inflation linked liabilities, purchase assets with a future value linked to the inflation rate.

In theory, LDI funds would have simply been able to buy fixed income or inflation linked government securities for all the necessary maturities. The reality was that it was often difficult to perfectly match assets against liabilities. There are not always sufficient bonds of the right type (fixed coupon vs. inflation linked) and maturity.

Collateral Management

Entering into derivative contracts meant the funds needed to perform collateral management processes with their counterparties. The introduction of Uncleared Margin Rules (UMR) meant most of these funds had to calculate exposures and exchange collateral on a daily basis (normally cash for variation margin). The potential volatility of both interest rates and the price of bonds (particularly relevant to gilt linked total return swaps) was clearly not anticipated when LDI strategies were designed.

Gaps in the maturity of available bonds could be filled by entering various types of derivatives including:

- Interest Rate Swaps where the fund swapped a floating rate interest to receive a fixed rate of interest.

- Inflation Swaps where the fund swapped a fixed rate of interest for a rate based on the changes in retail price index.

- Real Rate Swaps where the funds entered into a contract combining the interest rate and inflation swaps described above into a single contract.

- Gilt Total Return Swaps where the fund paid benchmark interest rate such as SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) and received the total return on gilts (coupon + changes in market value).

Repo

The final piece of the LDI puzzle was the use of repo. LDI funds were typically extremely long in gilts. Funds repo-ed out their gilts, in their billions, to provide cash to meet the margin calls on the LDI funds’ derivatives and to create more leverage to boost returns. Just as before the Great Financial Crisis, repo was used to not just mitigate the credit risk to lenders but also by borrowers to increase leverage. They bought bonds, repo-ed them out and in turn bought more bonds, sometimes repeating the cycle multiple times.

The Crash

The sudden crash in the value of gilts triggered flight, particularly by foreign investors who own around 30% of the UK national debt. This exodus also caused a fall in the value of sterling. Fearful of further capital losses from both falling bond prices and a collapse in the value of sterling, investors were prompted to sell more bonds.

This cycle had a particularly traumatic impact on LDI funds. Changes in derivative values, particularly the losses LDI funds experienced on gilt Total Return Swaps, led to large margin calls by banks from their LDI counterparties. Some LDI funds were able to call on the sponsors (the employers or former employers of members of schemes) for additional cash. However, many LDI funds were “Pooled Funds”, with no recourse to sponsors. They had no choice but to try to use their most liquid assets (their gilts to raise funds). Meanwhile in the repo market the fall in gilt prices were causing re-prices and margin calls, not to mention a reluctance to do reverse repos on a rapidly falling asset. The net result of all of this was funds had to start selling gilts to raise additional cash both for margin calls and to fill the funding gap caused by fall in the value of the collateral provided via repo.

The only apparent path open to the Bank of England to avoid collapsing the currency, destroying the market for government debt and wrecking a large swathe of the pension industry, was a large-scale intervention in the gilt market. The Bank started buying gilts and continued for over two weeks until the value of gilts and sterling recovered and then stabilised.

Conclusions

Repo and collateral management practices were not responsible for the LDI crisis but they did provide mechanisms for transmitting the impact. Historically, practices in collateral management were slower moving but the end result of margin calls on gilt sales would likely have been the same. The LDI strategy itself was clearly the more problematic aspect and the dependency of many funds on derivatives and additional leverage made the model inherently fragile. However, it was one of the most surprising lessons related to a previous series of reforms traced back to the Great Financial Crisis, in this case UMR. EMIR (European Market Infrastructure Regulation) and SFTR (Securities Financing Transactions Regulation) made it compulsory to report derivative and repo transactions to UK regulators. The main user of that data was the Prudential Regulatory Authority (an arm of the Bank of England) for macro-prudential purposes, i.e., looking for risks to the stability of the financial system, but authorities seemed oblivious. Perhaps the biggest lesson is for regulators: that having more data is not the same as knowing what to do with it.

For a more detailed analysis please have a look at the full paper in the Journal of Risk of Management in Financial Institutions, “Good Intentions in Risk Management and the LDI Crisis”.

About the Author

Martin Walker is the Head of Product Management for Broadridge’s Securities Finance and Collateral Management division. Former roles include Global Head of Securities Finance and Treasury IT at Dresdner Kleinwort and Global Head of Prime Brokerage Technology at RBS Markets. He has also worked as a consultant and researcher in capital markets with several papers published. He contributed to the new book, Evidence-Based Management – How to Use Evidence to Make Better Organizational Decisions, and his first book on Capital Markets infrastructure will be published later in the year. He has an MSc in Computing Science from Imperial College, London and a BSc in Economics from the London School of Economics. He is also a fellow of the Centre for Evidence-based Management.

Martin Walker is the Head of Product Management for Broadridge’s Securities Finance and Collateral Management division. Former roles include Global Head of Securities Finance and Treasury IT at Dresdner Kleinwort and Global Head of Prime Brokerage Technology at RBS Markets. He has also worked as a consultant and researcher in capital markets with several papers published. He contributed to the new book, Evidence-Based Management – How to Use Evidence to Make Better Organizational Decisions, and his first book on Capital Markets infrastructure will be published later in the year. He has an MSc in Computing Science from Imperial College, London and a BSc in Economics from the London School of Economics. He is also a fellow of the Centre for Evidence-based Management.