Late last month the OFR published a paper, “Regulatory Arbitrage in Repo Markets” by Benjamin Munyan (October 29, 2015) that got a decent amount of press. The paper looked at how foreign banks operating in the US squeezed down their tri-party repo book over statement dates. The interesting part was why those foreign banks squeezed down their repo books while US banks didn’t seem to do the same thing.

The term “window dressing” was tossed around a lot. The paper defined it as:

“…Window dressing is the practice in which financial institutions adjust their activity around an anticipated period of oversight or public disclosure to appear safer or more profitable to outside monitors…”

How big is this phenomenon? The paper said

“…that broker-dealer subsidiaries of non-U.S. banks use repo to window-dress roughly $170 billion of assets each quarter, in what appears to be a form of regulatory arbitrage…”

Why does this impact non-US broker-dealers? It has to do with how balance sheet and capital ratios are reported. US banks report at quarter-end but also have to produce a daily average number. Non-US broker dealers only report quarter-end. It makes a big difference to the optics. Just reporting quarter-end numbers won’t show balance sheet volatility to regulators. But the daily average numbers will put the exercise front and center. The daily average reporting for US Broker dealers makes the quarter-end exercise moot and is one reason that repo books have shrunk.

For years repo dealers aggressively managed the size of their repo books over statement dates. The first priority was to net trades down. The rules are basic: if trades are with the same counterparty, same settlement system, same end date, then trades in opposite directions can be netted off the balance sheet. This was an exercise that virtually all banks did over statement dates and it created all sorts of dislocations. The fire drill was time consuming and often annoyed clients.

“…U.S. banks report the quarter average as well as quarter-end balance sheet data and ratios, whereas non-U.S. banks only report quarter-end data. This regulatory difference seems to explain why U.S. bank dealers don’t window-dress: U.S. banks have little incentive to window-dress at the end of the quarter compared to any other time during the quarter…”

and

“…U.S. banks are required to report capital ratios for the last day of the quarter as well as an average across all days of the quarter. In contrast, non-U.S. banks can simply report for the last day of the quarter. Therefore, U.S. banks have very little incentive to window-dress their balance sheet at the end of the quarter—it will not affect their capital requirements any more than a deviation any other time in the quarter would…”

The reduce repo books, non-US dealers will tell their clients that they have to do trades that will net off the balance sheet (and make it appear like the non-US dealer is shrinking their book) or ask clients to close out trades. US dealers, in contrast, would have to do the netting exercise daily to get the same result.

The authors also found that non-US broker dealers tended to sell HQLA over the statements dates.

“…in the days preceding a quarter-end, dealers are on net, selling heavily to non-dealers (giving up assets for cash). However, once the new quarter starts, dealers are immediately relevering by buying back agency bonds…”

This sounds fishy to us. Taking the price exposure for a day or two seems foolish. The non-US broker dealers could be executing sell-buys, the old fashioned type of financing where a dealer simply writes a cash and a forward trade. Some repo agreements allow for margining of these deals, but it is hardly best practice. The other alternative is for a broker dealer to get rid of the cash positions synthetically, doing Total Return Swaps (TRS) along with cash sale. When the TRS is unwound, the dealer buys the paper back. That way they retain the economic exposure but not the repo balance sheet. The TRS will absorb a lot less balance sheet than a repo. Some broker dealers have been pushing the synthetic solutions more broadly too, a trend we expect to only grow.

The paper’s author also wanted to know if this was a cash supply issue. Could Money Market Funds, the primary source of cash in tri-party, want to avoid trading across statement dates or see seasonal withdrawals of cash? The conclusion was “no”. This does leave the MMFs with some excess cash, but the Fed’s RRP program appears to sop this liquidity up. Certainly some of the MMF cash prefers to show the Fed as counterparty over their reporting periods, but the study did not show this as a primary driver.

“…declines in repo borrowing due to window dressing leave cash lenders such as money market mutual funds with excess cash that they struggle to invest. My analysis of monthly money market fund (MMF) portfolios shows that despite being able to anticipate window dressing, MMFs are still unable to find any investment at all for about $20 billion of cash each quarter-end before September 2013…”

Which securities will the window dressing impact? It is concentrated in HQLA. This makes sense given that less liquid paper will have fewer balance sheet netting opportunities, clients get really annoyed if they have to find another source of financing for the less liquid paper for just a couple days, cash providers via TRS are harder to find for that paper, and there is some spread to pay the repo dealers not to throw them to curb. Dealers will often just leave those positions alone.

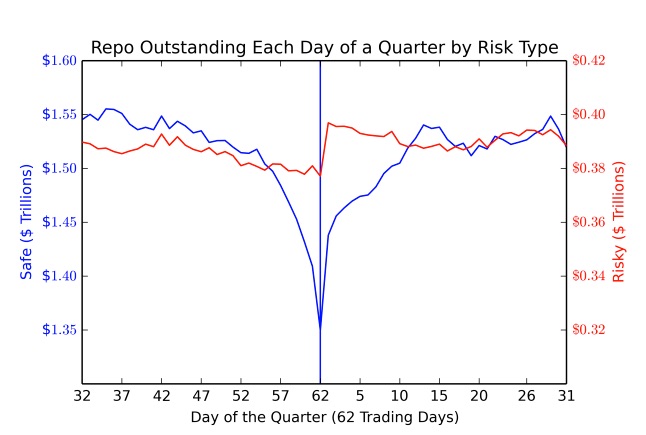

“…Just as the decline in repo is concentrated in non-U.S. borrowers, the decline is happening only in safer collateral, which is more liquid and easier to sell and then buy back for window dressing purposes. Window dressing by selling the riskier, less liquid assets would be costlier, and its effect on required ratios such as the net stable funding ratio is very similar…”

Source: “Regulatory Arbitrage in Repo Markets”

As an aside, NSFR doesn’t kick in for a while and we are not sure how many banks are managing to that yet.

The study seems to exclude non-bank dealers. We are not sure if this would make a big difference or not. It would, however, be interesting to see if the research could include any types of non-repo financing (e.g. TRS) as well as shadow bank involvement. These are potentially big gaps in the picture.

The reporting differences are allowing non-US banks to keep their repo businesses going, although at the cost of statement date balance sheet management. But since this was a common practice for years in the repo business, traders (and clients, who are happy for the financing in the first place) accept it as a cost of doing business.

Is this regulatory arbitrage? It is hard to argue against the notion that different treatment of broker-dealers, based on where they are from and differences in rules imposed by local regulators, doesn’t open the door for greater leverage on the part of non-US broker dealers and potential for systemic risk. We won’t be surprised if efforts are made to put all broker dealers on a level playing field.

This is not a new topic for Securities Finance Monitor or Finadium. Take a look at “Finadium: Netting Rules for Repo, Securities Lending and Prime Brokerage” (Sept. 25, 2104) or “Finadium: What the Buy-side Should Know About Netting” (February 23, 2015).