Hold the phone, a 15% Leverage Ratio? This was the plan released last week by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Before we explain how too far gone this proposal is, let’s slow down and check out its merits.

The Minneapolis Fed plan is meant specifically to limit the possibility of a Too Big to Fail (TBTF) financial institution crash to less than 10% over the next 100 years. The Minn. Fed notes that under today’s financial regulations, the possibility of a major bank crash has dropped by 84% to 67%, still too high for comfort. The only way to really reduce bank TBTF risk is by making banks hold substantially, and we mean very substantially, more high quality liquid asset

The plan takes the following steps:

1) Increase common equity capital for banks with assets exceeding $250 billion resulting in a Leverage Ratio of 15% (presumably as calculated under the current US and Basel rules) and a Tier 1 capital ratio of 23.5%.

2) Get the US Treasury to either say that a bank is no longer TBTF, in which case a Tier 1 capital ratio of 23.5% is fine, or else the bank has to meet a 38% Tier 1 capital ratio.

3) Tax the borrowings of shadow banks with assets over US$50 billion.

4) Reform community bank regulation.

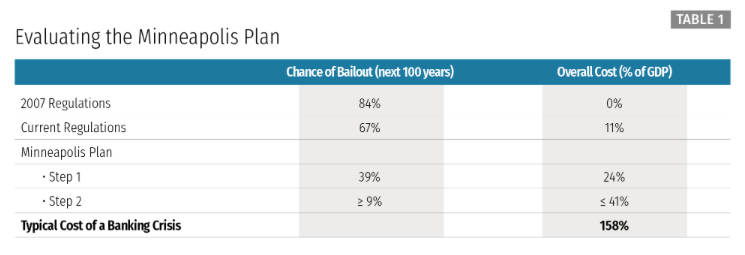

Below is the Minn. Fed’s summary of how the plan would change the risk of a bank bailout over the next 100 years vs. the overall cost to GDP. They’ve got a good point here: if the cost of a big bank bailout is 158% of lost GDP, then why not reduce that probability to under 9% over the next 100 years rather than leaving it at 67%?

Unfortunately, this plan ignores the reality that real people need to have real jobs to pay for real food. And not over the 100 year period but right now. The Leverage Ratio remains the main reason why banks are limited in their credit and maturity transformation businesses (i.e., the provision of balance sheet). Some limit on these businesses are good and appropriate, but we (unlike others) take the view that these limits have damaged the healthy functioning of capital markets by allowing excess volatility and reducing liquidity when it is needed most.

If the sole purpose of a bank is to take savings and perform credit and maturity transformation to make residential or construction loans, then so be it, a 15% Leverage Ratio will keep them safe. But the modern bank, especially a G-SIB, provides balance sheet for trillions of dollars of diverse economic activity that includes structured products (which in turn supports retail car loans and the like), hedge fund margin (which in turn supports market liquidity), and trade finance (which creates jobs).

We are not bank apologists for prior sins and are not much concerned about whether big banks make US$2 billion or US$2 trillion in annual profits. But fundamentally, too much restriction on bank activity chokes markets, which damages financial activity, which results in the inability of companies to raise capital, which means that real people don’t get jobs. That does not seem an acceptable trade off. Capital markets have been successful for a reason; excessive Leverage Ratios damage them for a good reason, but there must be a balance between risk management at banks and markets that work for the people.

Already, US regulators are considering lowering the 6% US Supplementary Leverage Ratio, concerned that this figure has constricted bank activity too far. Why move to 15%? A riskless society sounds great, but in practice it does not achieve other critical objectives for societal and economic development.

We appreciate the Minn. Fed’s plan as a theoretical objective. As a practical reality however, we think that a move downwards from the current 6% SLR is a much better idea than a move upwards to 15%, regardless of the expected risk reduction in the next 100 years.

Here’s the full Minneapolis Fed plan for ending Too Big to Fail.