The Fed NY report “The Risk of Fire Sales in the Tri-Party Repo Market” (May 2013) by Brian Begalle, Antoine Martin, James McAndrews, and Susan McLaughlin certainly caught our eye. Not surprisingly, we have some observations.

The authors define fire sales as “rapid sales of assets in large amounts that temporarily depress their market prices” and a “forced sale of an asset at a dislocated price”. Fire sales can “…amplify problems faced by a financial firm because the reduced sale price of the assets can result in realized losses that lead to a decrease in capital and the possible need for additional asset sales. Excessive sales by a single firm can also propagate stress to other institutions if they face margin calls and are forced to sell assets…” The paper argues that since tri-party is so big and some participants vulnerable to runs, that fire sales are likely when there is a default.

Tri-party has been the focus of regulators for a while. The daylight risk to the clearing banks caused by the unwind/rewind was the biggest issue and the primary focus of regulators. Poor liquidity and credit risk practices also plagued the market, according to the paper. By this (we think) they mean, among other things, remarkably static tri-party haircuts across a variety of asset classes while the financial crisis was swirling around them and lack of granularity in tri-party schedules that allowed for some volatile paper to slip in under the asset-backed category. Much of this has been fixed or is in process of being corrected. But still left over is the risk of fire sales.

There are two flavors of fire sales: 1) dealers selling paper they can no longer finance – a pre-default liquidation — and 2) cash providers, finding themselves long paper they don’t want (and didn’t expect) when a dealer defaults, opting to liquidate – a/k/a a post-default liquidation. The solutions to each problem are very different. Mitigating the dealer-side risk could be longer dated financing, thus reducing the vulnerability that comes with maturity transformation (especially on less liquid collateral). LOLR programs, which were very effective during the financial crisis, gave comfort to those lending cash that there would be money to pay them off. And finally the authors noted that capital and liquidity regulation could play a part to reduce dealer vulnerability. It sounds to us like LCR might address the liquidity issue already.

But what about the dealers defaulting on their tri-party and the cash providers ending up with paper? Will the cash lenders be able to handle it? How? The authors brought up LTCM, when a capital injection by the banks stabilized LTCM’s books, giving time to unwind positions without a fire sale. LTCM can be viewed as a good story — where cash was injected to buy time. Others were not so fortunate: Peloton, Thornberg, Carlyle Capital, and ultimately Bear Stearns were all cited in the paper as cautionary tales of contagion and panic.

The problem is that pesky risk paper — corporates, ABS, equities. Large, concentrated financed risk paper positions increase vulnerability to a fire sale. Just because paper is normally liquid, it doesn’t always stay that way. Any cash trader knows that illiquidity goes up exponentially on lower quality paper at the first hint of stress. Traders sell whatever they can under these circumstances, giving rise to contagion. At the moment, upwards of $300 billion of paper in tri-party is in the less liquid bucket.

What would push the cash lenders to sell first, ask questions later? Why couldn’t they hold on until markets calmed? Beyond their own potential liquidity issues (think: Reserve Primary Fund breaking the buck), the paper noted that the cash lenders, now securities owners, might not have the legal authority to own the underlying collateral or at least not as much of it. We have written about this before, calling it the question a cash lender never wanted to ask their legal department — for fear of being told they needed to manage the eligible collateral to their investment parameters. That is a technological nightmare (although it may be the only real way to fix the problem). Operationally speaking, selling large amounts of paper inherited in a default may simply be impossible without some serious outside help. The banks who bailed out LTCM had no such issues but the positions weren’t as (potentially) huge.

We note that this problem is actually exacerbated by tri-party reform. Squeezing down the unwind/rewind period means that cash lenders have collateral risk for more of the day – ultimately trending toward 24 hours less “an operational moment in time”. While it reduces the clearing bank’s risk, it increases the cash lenders’. We just hope everyone is paying attention to that shift and the risk ramifications.

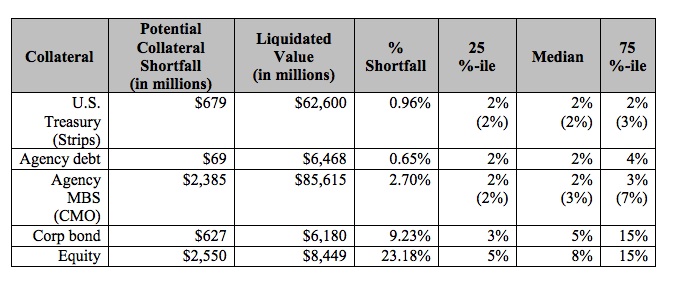

The paper takes in interesting look at liquidation timing. Calculating the number of days it would take to sell off a hypothetical portfolio of $200 billion (the sample size of a large dealer’s tri-party financing book), they find it could range, based on typically traded volumes, between 9 days for US Treasuries and Strips to 30 days for ABS. Corporate bonds, for example, came in at 27 days. Overlaying VaR to that process results in some idea for the magnitude of losses that could be incurred. If the defaulted portfolio is sold down at a steady rate (implied by the liquidation timing) assuming prices implied using 120- day volatility over the Sept 2 to Dec 31, 2008 period, a calculation can be made of how much cash could be lost. With a 99% confidence, shortfalls ranged from .96% for US Treasuries to 23.18% for equities.

We found it strange that haircuts weren’t mentioned in the calculations. Repo traders would look at this stress exercise and think it was being done to determine how much haircut to take. Losses for cash lenders are post-haircut and that, it appears, was ignored. We also wonder about changes to liquidity during stress. The paper did acknowledge that assets like US Treasuries are in high demand during a period of stress, thus easier to sell. But what about equities? Volatility in equities markets seems to increase volume, perhaps making it easier to sell that paper faster. The trouble spots are corporates, private label MBS, and ABS – where stress causes liquidity to evaporate.

The paper outlines some suggestions for dealing with pre- and post-default liquidation. We will focus on post-default ideas. The authors suggest that an agreement between dealers to form a consortium to buy out government paper from the cash lenders (should there be a dealer default) could mitigate the risk of a fire sale. We wonder how that would work and if it isn’t just passing the hot potato? The paper says “the consortium dealers have the knowledge and ability to manage large portfolios of such securities” – we certainly hope so. They did in LTCM. The authors suggest that since the consortium members will still be solvent, that they will have continued access to tri-party funding. This is despite the presumed crisis engulfing the market at the time and uncertainty about who ended up with enough illiquid paper to sink themselves. This might be ok if the funding problem has idiosyncratic roots, but we wonder about (what amounts to) mutualization when the risk zips past the tipping point and goes systemic.

For risk assets, the paper suggests a single entity – a centralized liquidation agent — taking on all the paper and selling at a controlled pace, perhaps in a series of auctions. While this does control everyone running for the doors at once and the chaos that comes with that, it still does not mean the losses won’t be enormous – even if the seller can do so over time. The overhang of supply will still be there. And in the middle of all of this, decisions will have to be made about what assets are impaired and getting worse versus those that are going to bounce back. This is easy to do after the fact, but in the fog of war (our new favorite metaphor) we wonder.

The paper does acknowledge that risk assets may need higher haircuts to mitigate falling values. They also mentioned the possibility of a CCP specifically for repos against risk assets. Is that an idea that will have legs? Another concept mentioned was a repo resolution authority with the power to claw back losses (from liquidation). Finally, “an ex post emergency central bank liquidity backstop for the dealer’s creditors” was examined. The weaknesses of this approach will sound familiar: moral hazard and difficulty in getting a facility set up quickly enough.

This is an interesting paper. With all the stuff we have heard as of late about funding shock — from the FSOC to Fed Governor Tarullo (see yesterday’s post here), we can’t help but think this paper is serving as the intellectual backbone behind a lot of it…to say nothing of the shape of regulation to come.

A link to the Fed NY paper is here,