The Fed has released the latest capital rules for Global Systemically Important Bank Holding Companies (GSIBs). One critical part of this set of rules is the inclusion of a second calculation methodology that includes the degree of dependence on securities financing trades. Banks will be subject to the higher of the two calculations when determining their capital conservation buffer. The Fed has been projecting the need to protect against repo runs in a crisis for a while and this is it. This is Part I of a two part post.

At first glance, it seems benign. There are 8 US banks that have qualified as GSIBs – BofA, Citi, Goldman, JPM Chase, Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, BNY Mellon, and State Street. In what has been reported as something of an unintended blurt by Fed Vice-Chair Fisher, only JPM Chase has a capital shortfall under the rules, although it is a doozy ($22 billion). According to a December 9, 2014 FT article by Tom Braithwaite and Gina Chon, “JPMorgan faces $22bn capital hole under new Fed rules” (sorry, behind the pay wall), JPMC could handily fund the shortfall out of retained earnings.

Given all the moving parts in the calculation, it is impossible to say how much of the capital deficit can be attributed to securities financing business. But since all the GSIBs will want to avoid bumping up their capital conservation buffer, and SFT are specifically included in the second calculation, there will be even more focus on businesses like repo and sec lending to keep their head down.

Why the focus on short term funding? From the report:

“…The financial crisis also revealed dangers that can emerge as a result of firms’ reliance on short-term wholesale funding. Short-term wholesale funding is used by a variety of financial firms, including commercial banks and broker-dealers, and can take many forms, including unsecured commercial paper, asset-backed commercial paper, wholesale certificates of deposits, and securities financing transactions. During normal times, short term wholesale funding helps to satisfy investor demand for safe and liquid investments, lower funding costs for borrowers, and support the functioning of the financial markets. During periods of stress, however, reliance on short-term wholesale funding can leave firms vulnerable to runs that undermine financial stability…”

and

“…A GSIB may opt to modify its funding profile to reduce its use of short-term wholesale funding, or continue to use short term wholesale funding to the same degree but hold additional capital…”

The message is: either a bank tightly controls “runnable” funding sources like repo, or they need to hold more capital. Seems like an example of Hobson’s choice.

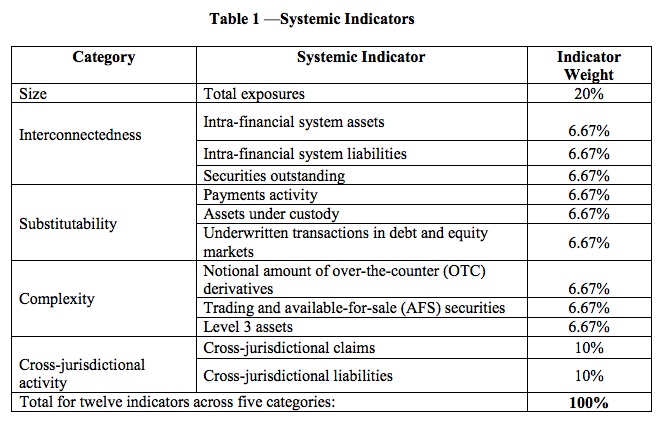

How is a bank determined to be a GSIB? Measurements for five proxies that are seen as drivers of systemic risk — size, interconnectedness, cross-jurisdictional activity, substitutability, and complexity – will be established. Once a bank crosses into GSIB territory (by scoring above 130 points on the test), they have to do two sets of calculations to determine how much extra capital they need. The first test is a repeat of the qualifying calculation. But the second set includes SFT (although it takes out the substitutability measurement). The higher of the two numbers will be used. It is expected that the calculation which includes SFT will generate a higher number than the first test method.

Next week we will continue with our look at the Fed’s capital rules and examine how the calculations are done.