Asset management may be considered a profitable business but the trend has recently been moving in the opposite direction. A new raft of challenges, ranging from MiFID II to the growth of passive investment strategies, has asset managers looking at cost optimisation in a new light. This article considers some of the headwinds and opportunities for cost controls in the asset management sector.

Which way are asset management profits heading?

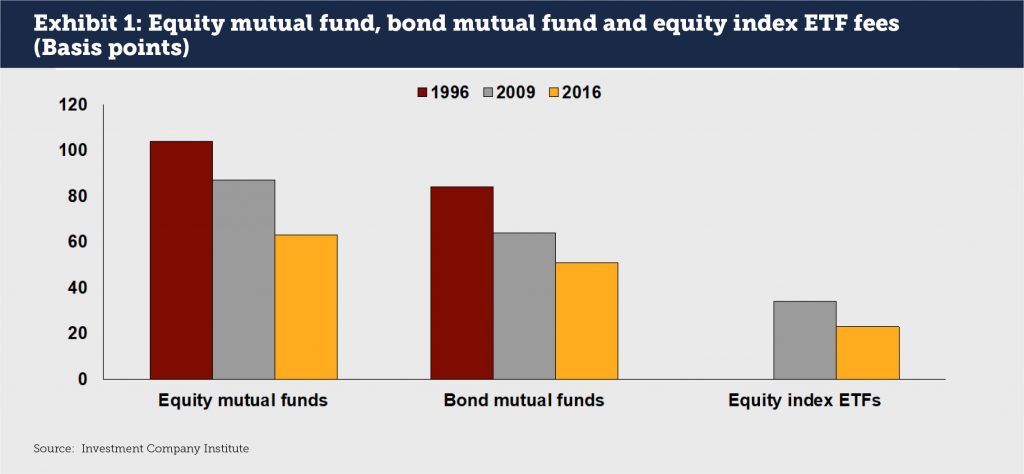

On the surface, the asset management business looks healthy. Research released by the Financial Conduct Authority in 2016 and 2017 showed profit margins of 35% between 2010 and 2015, prompting some oberservers to ask if asset managers were too profitable.[1] However, more recent evidence suggests that profitability margins are not what they used to be; data from the Investment Company Institute show declines in fees for equity, bond and ETF portfolios from 1996 to 2016 (see Exhibit 1). The new question is not whether asset managers are too profitable but rather what they can do to reduce costs in a climate that is rapidly becoming more complex.

Our conversations with clients suggest that most firms are concerned about maintaining profitability. This is not idle chatter: there are new factors in the market that require close attention not just in day to day costs but to the asset management business model in general. With some projections reaching a 30% decline in profitability over the next few years, asset managers must take action to ensure the viability of both individual products and their franchises in the new regulatory, service provider and technology environment.

MiFID II: the asset management big bang

While regulations in general are creating additional administrative burdens on asset managers, MiFID II is the most likely to have a major long term impact on both costs and business models in Europe and globally. The first Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) was originally introduced in 2007 to regulate the provision of services to clients linked to financial instruments and trading venues. From January 3rd 2018, a revised set of legislation and a new Market in Financial Instruments Regulation (MiFIR) will go live; collectively these rules are known as MiFID II. Some of the known impacts of MiFID II on the asset management industry are:

- Research will no longer be allowed to be bundled with dealing commissions by banks and brokers. Instead, most research will be paid via a separate research payment account, where the budget for research and the charges will be transparent to customers. Research paid for this way will also have to be periodically reviewed for quality.

- Firms will be expected to “execute orders on terms most favourable to the client”, a requirement that makes sense on stock exchanges but creates confusion and complications in non-liquid markets including repo and securities lending. Reporting data, such as valuations, to clients will need to increase in frequency.

- New rules are included regarding governance and the management of asset managers. Complaint handling processes will have to be extended to professional and potential clients and firms will require a formal complaints management policy.

- Title Transfer Collateral Arrangements (TTCAs) with retail clients, which allow the transfer of asset title for collateral purposes, will be forbidden.

- Strict new rules will be imposed on funds that have algorithmic and high frequency trading as part of their trading strategy.

- A reclassification of FX Forwards imposes additional work in trade reporting and collateral management.

And these are just the known impacts.

The growth of passive asset management

The assets under management (AUM) of actively managed funds still far exceed those in passive funds including both conventional tracker funds and ETFs: Morningstar estimates US$23.9 trillion for active versus US$6.7 trillion for passive. However, new investments have predominantly flowed into passive funds over the last few years and the trend is accelerating. While the move to passive has occurred faster in the US than in Europe, the same shift is taking place in both regions.[2] Moody’s Investors Services estimates that passive strategies will account for over half of AUM in the US within four to seven years.[3] Moody’s expects that growth in Europe and Asia will also grow steadily.

The reasons for this shift are straightforward. An investment product that passively tracks an index at a low cost can provide benefits to investors, especially when those products can beat actively managed funds. An opinion piece in Bloomberg recently estimated that Vanguard alone has saved investors $175 billion in fees since it was founded in 1974.[4]

Responses to cost pressures

While the squeeze on revenues and increased compliance costs has become intense, asset managers have a number of levers available to improve margins. Industry service providers including banks, CCPs and processing utilities, offer services that place an individual manager’s custom services onto a shared platform. This effectively allows many managers to share the cost of one infrastructure. These services have grown to encompass the majority of what asset managers do outside of actual investment decision making, including custody banking, fund administration, box management, fund accounting, Know Your Customer (KYC), collateral management and middle office. Even asset managers are looking to be utility providers: last year Pimco announced it was rolling out KYC.com, and BlackRock aims not just to be a fund manager but a provider of an “operating system for investment managers” through its Aladdin platform. Some buy-side firms have also been active in joining collaborates to explore new technologies such as Distributed Ledger Technology.

Even where an asset manager has the scale to build the systems and processes required to support their own suite of operational support, it can make sense to look outside because the service provider may have greater economies of scale and the benefits of specialisation in those areas. Since many of these services are essentially commodities where cost and quality are measurable, all options should be considered, so long as service providers can be regularly benchmarked. Outsourcing also provides a high degree of transparency in cost management, which will be critical for MiFID II reporting going forward.

Asset managers are pursuing mergers and acquisitions as one solution to cost management. October 2016 saw the £5 billion merger of UK based Henderson and US firm Janus. December 2016 saw the purchase by France’s Amundi of Pioneer Investments from Italy’s UniCredit SpA for €3.6 billion. March 2017 saw the announcement of an £11bn all-share (and all Scottish) merger of Aberdeen Asset Management with Standard Life. It has been argued that cross border mergers create the opportunity for global expansion and broader product offerings to existing customers, but it is also clear these mergers create the opportunity for increased cost reduction and a general scaling up to survive in a market that is increasingly dominated by giants such as Vanguard, Fidelity and BlackRock. If economies of scale through outsourcing reduce costs, then economies of scale through larger books of business also reduce costs.

While MiFID II generally mandates best execution, asset managers will need to work with their peers, their service providers and third parties to identify what their fiduciary responsibilities are outside of publicly traded exchange products. As anyone struggling with MiFID II knows, it is not always easy to use transaction data to clearly identify who is the best party (or platform) to trade through. The Financial Conduct Authority’s Asset Manager study found that “On trading and execution costs, for example, we found that most firms do not have adequate management focus, front office business practices or supporting controls to meet our current requirements on best execution”.[5] This will be an industry challenge going forward.

Every asset manager trading with a European counterparty needs to pay attention to this matter from both the regulatory and cost perspective. The overall level of spending on execution can vary considerably even between funds pursuing similar strategies; this suggests there is scope for improvement. On the other hand, the need for transparency means that cost in terms of fees from brokers may not be the only consideration; the ability of a broker to provide granular data in a timely manner to meet regulatory requirements will become an increasingly important factor in relationships.

2017 marks a point when the asset management industry needs to make fundamental changes in cost optimisation. Overall, it is still a highly successful industry and the level of assets under management is likely to see continued growth. However, regulatory compliance will need to be built into systems and process, and will become a key part of the offerings of service providers. Cost control based on vigorous data analytics will become a daily part of life. Active fund managers will have to show both innovation and performance in a world increasingly dominated by large passive managers. Asset managers that take a proactive position on cost optimisation now will be best positioned to succeed in the future, regardless of how large their assets under management.

James Treseler is Global Head Cross Asset Secured Financing at Societe Generale.

[1] “Asset Management Market Study: Final Report,” Financial Conduct Authority, June 2017, available at https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/market-studies/ms15-2-3.pdf

[2] In their June 2017 Asset Management Market Study, the UK Financial Conduct Authority estimates that 30% of US assets are in passive funds compared to 20% of UK assets.

[3] “Moody’s: Passive investing to overtake active in just four to seven years in US; global traction to pick up”, Moody’s, February 2, 2017, available at https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Passive-investing-to-overtake-active-in-just-four-to–PR_361541

[4] “How the Vanguard Effect Adds up to $1 Trillion,” Bloomberg, August 30, 2016, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-08-30/how-much-has-vanguard-saved-investors-try-1-trillion

[5] “Investment managers still failing to ensure effective oversight of best execution,” Financial Conduct Authority, May 18, 2017, available at https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/multi-firm-reviews/investment-managers-failing-ensure-effective-oversight