The Richmond Fed recently published a report on the extent of potential government bailout exposure in the event of another major financial crisis. The estimate shows that the US government remains in the bailout business, like it or not.

According to the report, “Bailout Barometer: How Large is the Financial Safety Net?,” by Liz Marshall, Sabrina Pellerin, and John Walter, “the share of private financial system liabilities for which the federal government provides protection from losses. In addition to protection provided by explicit government guarantee programs, the estimate includes implicit protection that people are likely to infer from past government actions and statements. Despite efforts to end ad hoc bailouts, the financial safety net that protects certain firms remains large under current government policies.”

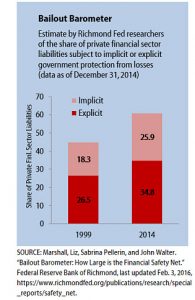

Some of the data are pretty eye popping. According to the report, the federal government’s “financial safety net” covers nearly 61% of the financial sector. While the report analyzes data from the end of 2014, it likely remains indicative of the current state. What is most interesting is the extent to which there are “implied” protections and how we have moved in the wrong direction since the crisis (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Richmond Fed Bailout Barometer

A major concern of regulators over the last decade has been that the financial services industry (and the public) has long operated under a basic assumption that the federal government is the ultimate backstop in the event of a crisis. The financial services industry has been roundly criticized for counting on Fed and other central bank support under worse-case scenarios, leaving institutions free to take on undue risks. Before 2008, no one in financial services would have ever expected that governments would allow any important institution to fail. There was a certain unspoken operating tenet that if there was going to be a failure, it was better to fail catastrophically – because then you could be bailed out.

Most of the outcry over the Bush and Obama administrations’ response to the 2008 meltdown was over the use of public money to maintain the solvency and liquidity of private institutions. In retrospect, of course, we have found that governments have come out flat or even ahead on their emergency investments, but the vast majority of public opinion is that the private financial sector should not count on a repeat of the process “the next time.” Much of the regulation worldwide has been undertaken with the expressed intent to reduce governments’ exposure to private risk.

And yet, here we are despite all this. The bailout barameter really raises the question of what happened to getting governments out of the bailout role and private institutions to take better care of their behavior? Here’s part of the reality that explains the picture: regulation as it has developed has not created a more secure and more risk-dispersed system. It has simply limited the ability of banks to function on a large scale efficiently and, in fact, has driven most of the ultimate risk into the hands of the central banks. Why? Because central banks are the only ones left who can operate on the vast scale that is the real way the system works. They are mainly exempt from the rules governing the private financial system.

Unfortunately, the bailout barometer is another indicator that while regulations have reduced bank risk, they have not recognized or solved some of the more fundamental problems in the market. In a crisis, governments are still on the hook as lenders of last resort.