These are legitimately complex times for hedge funds. Between macropolitical turmoil, negotiating fees and managing their daily activities, hedge fund managers must pay attention to a wide range of factors that have direct and indirect impacts on their business expenses. Nowhere is this truer than in trading and investment strategies: the way that hedge funds invest and actually make money must be carefully evaluated to ensure that it still makes sense as regulatory changes occur. When the dust eventually settles, hedge funds must ensure that their strategies are still sound.

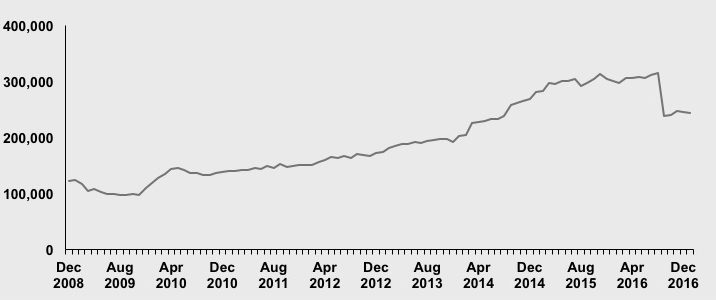

Leverage, both in borrowing from prime brokers and in derivatives, remains a key component of hedge fund trading strategies. Data from the European Central Bank shows that assets held by hedge funds in the euro area tripled from 2008 to 2016, but this understates the importance of leverage for hedge funds and the markets in general (see Exhibit 1). Recent estimates from the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority and the International Organization of Securities Commissions show leverage from prime broker financing at 1.3X – 3.27X across major markets, while synthetic leverage is 7X – 14X times of hedge fund NAV.[1] If hedge funds require this level of leverage, anything that impacts access is certain to make an impression on returns.

Total assets held by hedge funds in the euro area

(EUR millions)

Source: European Central Bank

Regulatory reform impacts hedge fund profitability

While the array of actual and potential regulations facing European and global hedge funds is vast, there are several factors to look at that directly impact hedge fund profitability. The first is the imposition of the Leverage Ratio, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) – the big three of Basel III.

Charting the increasing reach of the Leverage Ratio has a direct correlation with bank balance sheet availability. While the US, Canada and Europe have implemented a Leverage Ratio, most Asian jurisdictions have not. Even where the ratio currently is in place, it can always be altered up or down in the future. The higher (and more tightly defined) the ratio, the less balance sheet banks have to deploy, and conversely, a lower Leverage Ratio means that banks have more available capital. Likewise, some jurisdictions require a daily calculation of the ratio while others require only an end of quarter calculation, allowing for more flexible balance sheet deployment intra-quarter.

Hedge funds should pay close attention, especially when a Leverage Ratio has been announced but regulators have provided loopholes or even an entirely new definition of leverage that changes the outcome of the calculation altogether. A US version of Dodd-Frank Reform, for example, proposes to do away with the concept of risk-weighted assets when calculating the Leverage Ratio, among other changes.

While the LCR is now in place almost globally, and regulators have been consistent with its implementation, the NSFR remains outstanding business. The Basel Committee notes that 84% of banks can meet the NSFR today and Societe Generale is fully compliant. Implementing the NSFR globally however may result in banks having to change their behavior and counterparty decision making. Both the numerator and denominator of the NSFR have risk weights that impact the final calculation; transactions with hedge funds have worse risk weights than the same transaction with a government entity. As a result, banks will always prefer the government trade to the hedge fund trade, all else being equal. NSFR minimum standards are expected to come into force in January 2018, and these sorts of regulatory-driven imbalances will impact client profitability.

While new regulations are difficult to manage, there are some silver linings. At Societe Generale, we have found that the trading we used to do with other major banks is no longer viable; instead, the best balance sheet friendly business for us is with clients including hedge funds and asset managers. The push generated by balance sheet requirements means that we have become more focused on the interests and challenges that these clients face. In fact, we have to be, because that is now a primary source of revenue in place of what used to be bank to bank activity. As one tangible example, our prime brokerage balances have increased exponentially in the last several years, and hedge funds now have access to the 130+ markets that we used to reserve for mostly our own proprietary trading activities.

Hedge funds can find physical financing away from banks but should proceed with caution

As the financing market matures, hedge funds should be looking at physical leverage on central counterparties (CCPs) and Direct or Peer to Peer networks. This does not mean that every CCP and counterparty wants to do business with a hedge fund, but the opportunities are expanding. We expect that they will be increasingly important going forward. Hedge funds should evaluate these options while taking care to understand the models, what they get, and what they lose.

CCPs are offering several ways for hedge funds to become direct members to access physical financing. Just like in any derivatives transaction, a hedge fund arranges a securities lending or repo trade and the trade goes to the CCP for clearing. In some cases, the hedge fund is a direct member of the CCP, with a broker guaranteeing performance and managing risk on the CCP’s and client’s behalf. In other cases, a broker will sponsor a hedge fund for access; all transactions go through a broker just as in a derivatives trade today. CCP models are quickly attainable for hedge funds to gain leverage but still require some further development to prove their mechanics.

Getting active on a Direct, Peer to Peer or All to All trading platform can be more complicated. There is no CCP on these platforms, meaning that every counterparty is responsible for its own credit risk; the other side of the trade needs to approve the hedge fund as a credit counterparty. A bank may be happy to face a hedge fund but a pension fund, insurance company, or asset manager may be less inclined, or even unable to as a matter of policy, to have a hedge fund as a trade counterparty. A broker can still manage all the operations and mechanics for a hedge fund, and even find potential counterparties, but the final credit approval process will rest with the hedge fund and its counterparty directly.

CCPs and Direct, Peer to Peer, or All to All are less mature options for hedge funds to find leverage that will coexist with bank leverage and derivatives. None of these should be considered an exclusive route to market, but all should be thought through and incorporated as a hedge fund plans out its financing and cost management strategy over time.

Trading and cost management

Across physical financing, listed and OTC derivatives, access to the right strategies remains possible but at a cost. A principal challenge for clients is how to determine what that cost is and how to minimize it. Hedge funds have always sought pricing across multiple banks before making a trade, but that effort is now compounded by balance sheet and liquidity hurdles, along with regulatory reporting that may be required as a fundamental part of the trade. There is no easy solution for this besides incorporating big data into a technology suite that can measure comparative costs across products and counterparties.

More often than not, we find that the largest funds are equipped to manage these costs internally while small and mid-sized funds may not realize the extent of the problem. Some funds think that these costs are the bank’s problem, and in the case of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio or Net Stable Funding Ratio, that is correct. However, there are other regulations that fall on the shoulders of asset managers directly, for example MiFID II best execution requirements.

Under MiFID II, asset managers are themselves required to prove best execution: “When executing orders or taking decision to deal in OTC products including bespoke products, the investment firm shall check the fairness of the price proposed to the client, by gathering market data used in the estimation of the price of such product and, where possible, by comparing with similar or comparable products.” (MiFID II, Chapter III, Section 5, Article 64, Paragraph 4)[2]. This is a task that can be outsourced to a bank or other service provider but it carries a direct and tangible cost to provide the information, one way or another.

Costs are increasing for hedge funds both directly and indirectly, but there are positive outcomes. Bank regulatory reform means higher balance sheet costs but in Societe Generale’s case, this comes with a new focus on the specific concerns of prime brokerage clients. Non-bank markets for securities finance carry new opportunities and may become a viable means of accessing leverage, sometimes with the support of a bank to manage operations and valuation. The costs of trading are increasing but with smart access to data and technology, some of these costs can be mitigated. These are the roads forward for hedge funds in managing their costs as regulatory regimes continue to evolve.

James Treseler is Global Head Cross Asset Secured Financing at Societe Generale.

[1] “Report on the third IOSCO Hedge Fund Survey,” IOSCO, December 2015, available at https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD515.pdf

[2] “Commission delegated regulation (EU),” European Commission, April 2016, available at https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/3/2016/EN/3-2016-2398-EN-F1-1.PDF