An August 20, 2012 post in the New York Fed’s Liberty Street Economics blog is worth a read. Entitled “The Fed’s Emergency Liquidity Facilities during the Financial Crisis: The CPFF” by Tobias Adrian and Ernst Schaumburg, the article covers the liquidity provided to both non-financials and financials by the Fed during financial crisis via the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF). We take a look at the post and the program. We have some opinions to share, too.

Most of the focus on the funding that the Fed did during the financial crisis was on banks and broker/dealers. But corporate America was profoundly impacted too. The CPFF provided liquidity to corporates when the CP market screeched to a halt. We are reminded of the scene in “Too Big to Fail”, the HBO movie about Lehman, when Treasury Secretary Paulson gets a call from Jeff Immelt, GE CEO. Immelt complained that credit markets were shut tight and GE could not finance their daily operations.

The problem was that corporations, like financials, borrowed money in the CP market and had massive rollover risk. Like financials playing the borrow short/lend long “maturity transformation” game, corporation’s assets couldn’t necessarily be liquidated at a moments notice. When the Reserve Fund wrote down their Lehman paper and broke the buck, the CP market stopped in tracks, freezing short term financing. On October 20, 2008 the Fed announced the CPFF. It was in place until February 1, 2010.

One interesting thing about the CPFF was the how it was structured. First of all, the program only lent cash to highly rated borrowers (A1/P1). Rates were set to be higher than historical norms, but not too high. From the post: “…On the one hand, if rates were set too high, imposing high costs to borrowers, the CPFF would not provide significant relief to the market. On the other hand, if rates were set too low, companies might decide to opportunistically finance commercial paper through the CPFF, even after the normal functioning of the commercial paper market returned. The Fed therefore purchased unsecured commercial paper at an overnight interest rate plus 100 basis points, with an additional 100-basis-point credit surcharge for most unsecured borrowers, and purchased ABCP at a rate of 300 basis points above the overnight rate. The spreads of 200 and 300 basis points were significantly higher than historical spreads, ensuring that these rates would discourage financing through the facility except during very stressed market conditions…” On top of the cost to borrow, there was a 10bp fee charged as a “registration fee”, much like a bank’s commitment fee.

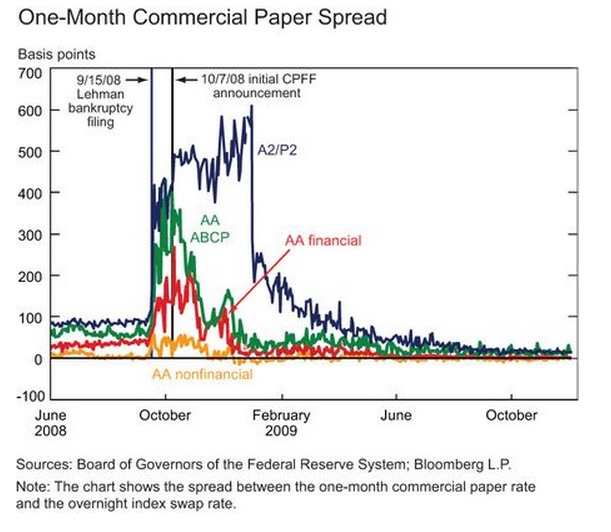

Here is a graph from the post showing spreads before and after the CPFF announcement. Notice how A2/P2 spreads (those issuers were not eligible for the CPFF) remained high.

The program was designed to backstop the availability of cash, but not make it the preferred source. The CPFF, at its peak, was 20% of the CP market. The Fed tried to avoid moral hazard issues while still remaining the lender of last resort. Compare that to the LTRO, the ECB’s repo program that poured cheap cash into the European Banks. The Fed acted with great skill when they created the CPFF and, while the counter-factual is always hard to prove, things would have been much worse if they did not have the flexibility to do it. Dodd-Frank takes a lot of that away. While the legislation may achieve the goal of “no more bailouts”, we wonder at what cost?

A link to the post is here.